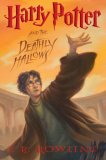

I finished Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows last night, and all I will say is… wow. It was amazing. I loved it. It was my favorite of the series, and possibly, I have to say, my favorite book ever.

I finished Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows last night, and all I will say is… wow. It was amazing. I loved it. It was my favorite of the series, and possibly, I have to say, my favorite book ever.

I won’t post a review here. I have a Harry Potter blog, and I will be posting whatever thoughts I want to share about the book over there. I do want to wait until this weekend in order to avoid spoiling it for others, but frankly, after the book has been released, I say it’s fair game for discussion. Pop on over there if you are interested.

I wish I didn’t have so much summer reading to do! I want to start over again from the first book to the last. That’s a project that will have to wait.

Thanks so very much for the wonderful books, Jo.

[tags]harry potter, deathly hallows[/tags]