I have to admit this book surprised me by the end. Partway through it, I was having trouble keeping going with it because I really wasn’t all that interested in Cath’s burgeoning interest in Jest. He’s your classic YA-novel charmer, and if I’m being honest, I’m bored with that guy. I assume the book’s audience (teenage girls) would find that part of the story more interesting than I did. However, after Cath bakes a pumpkin cake to enter into a baking contest with some devastating results for a new turtle friend of hers, the story grows more interesting. Cath is drawn to travel to the neighboring (and mythical) land of Chess to help Jest and Hatta (the Mad Hatter) in their quest, and she meets her fate precisely because of her heart—her inability to be heartless and put her mission before her loved ones. At that point in the story, I found it more difficult to put down and finished the book in one gulp. I admit this book was sitting on three stars for me until the last half, so my advice is if the premise intrigues you, but you are not digging it yet after 50 pages or so, maybe give this one longer.

I think I would have enjoyed the story even more had I re-read Alice in Wonderland first. Meyer brought in all the important characters and elements from that book and also explained the origins of few of those beloved characters as well. I know some of the references went over my head because it’s been too long since I’ve read Alice in Wonderland.

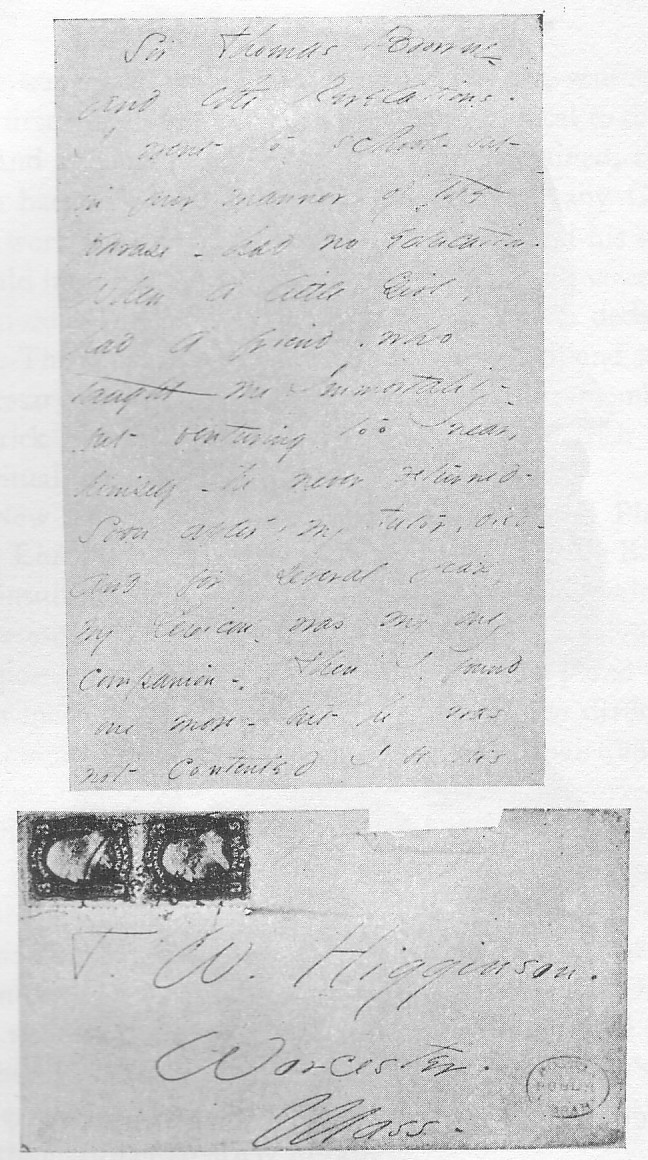

Meyer says this book began when she wished aloud to her agents for Gregory Maguire to “write the origin story for the Queen of Hearts.” Her foreign rights agent Cheryl Pientka replied, “Marissa, why don’t you write it” (453). I think some of the best books are born when writers wish the story existed, and because it didn’t, they decided to create it.

I haven’t read any of Meyer’s other YA books, though I understand they are popular, and she has sold film rights to the first of her Lunar Chronicles, Cinder. YA books certainly have become hot Hollywood properties lately. I am not sure if I’ll read Meyer’s other books. I might not have read this one had it not arrived in my Owl Crate box with a special edition just jacket just for Owl Crate subscribers back in November of last year. My copy is going right into my classroom library, where I know some of my students who like fantasy may enjoy it.

Rating:

Because this book’s been on my backlist since it arrived in November, I’m counting it for the Beat the Backlist Challenge.