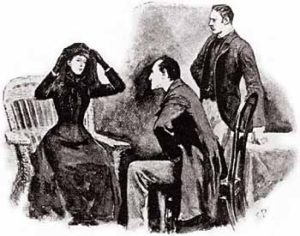

This week’s story in the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge is one of the most famous in the Holmes canon, “The Adventure of the Speckled Band.” A mysterious woman in black arrives early in the morning to ask for Sherlock Holmes’s help. She is terrified because her twin sister died under mysterious circumstances a few years prior, and she now finds hints that history is about to repeat itself. Holmes agrees to take on her case. The woman’s stepfather shows up shortly after she leaves to threaten Holmes, who is not in the least perturbed, and Holmes and Watson travel to the estate where the young woman lives with her stepfather. After investigating the room where the woman sleeps and her stepfather’s room, Holmes believes he may know what is happening, but he and Watson keep a vigil in the woman’s room that night to be sure.

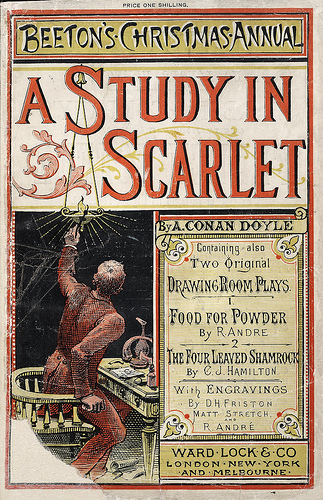

I actually remembered most of the details of this story, though I hadn’t read it in over 20 years, which I think is a testament to the story’s strength. If I have one quibble, it is once again we see a British prejudice about the tropics being a breeding ground for a passionate temper. It’s probably too much to expect a Victorian writer not to display the prejudices of his era, though, and it’s not as bad as A Study in Scarlet‘s portrayal of Mormons. Also, it seems that Doyle was making up fictional snake breeds, but that doesn’t surprise me much. He is a storyteller, and it’s not like he had Google at his disposal. The swamp adder doesn’t jump out as a particularly false note, but it is true that even herpetologists have been stumped as to which snake Doyle might mean. On the other hand, this is one the stories in which the reader has all the details needed to solve the crime and can deduce alongside Holmes, if the reader is paying attention. I do feel some Holmes stories are a bit of a cheat in that we don’t have the information Holmes does, but in this case, we can put the probable scenario together in our heads, for the most part, as Holmes himself solves the mystery, and it may be for that reason that this story is so popular. The BBC series Sherlock chose not to adapt this story, but it is alluded to in the episode “A Scandal in Belgravia” as “The Speckled Blonde.”

Rating:

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the fourth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Yellow Face.”

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the fourth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Yellow Face.”