Selected Letters by Emily Dickinson, Thomas H. Johnson

Selected Letters by Emily Dickinson, Thomas H. Johnson Published by Belknap Press on March 15th 1986

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

When the complete Letters of Emily Dickinson appeared in three volumes in 1958, Robert Kirsch welcomed them in the Los Angeles Times, saying "The missives offer access to the mind and heart of one of America's most intriguing literary personalities." This one-volume selection is at last available in paper-back. It provides crucial texts for the appreciation of America literature, women's experience in the nineteenth century, and literature in general.

When I studied the life and poetry of Emily Dickinson this summer in Amherst, this collection of Emily Dickinson’s letters was one of my required reads. I didn’t finish it before the course began, so I decided it pick it up again to finish before the year closed. Consider it a way to pick up a few loose threads.

As Dickinson says in a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, her mentor and friend as well as early editor, “What a Hazard a Letter is!” While this volume is not a comprehensive collection of Dickinson’s letters, it does include a broad selection dating from Dickinson’s preteen years to her final letter to her cousins Frances and Louisa Norcross right before she died. Many of her letters to Thomas Wentworth Higginson as well as the mysterious “Master” are included. Emily Dickinson seems to be the kind of person about whom the more one learns, the more enigmatical she becomes. Her writing is often a riddle. I wonder what her correspondents made of her. She seems to have taken a great deal of care to write to loved ones, particularly when they were grieving, and toward the end of her life, her letters paint the picture of someone buffeted from too many losses, beginning with the loss of her father in 1874 to that of Helen Hunt Jackson, a friend and admirer of Dickinson’s who insisted that Dickinson publish her work:

You are a great poet—and it is a wrong to the day you live in, that you will not sing aloud. When you are what men call dead, you will be sorry you were so stingy. (Letter 444a)

Dickinson writes beautiful letters, which should surprise no one familiar with her poetry, but it’s interesting that her letters are in some ways as impenetrable as her poetry can be. One that makes me scratch my head, to her sister-in-law (and some say her lover) Susan Gilbert Dickinson, includes the line, “Could I make you and Austin [Dickinson’s brother]—proud—sometime—a great way off—’twould give me taller feet—” (Letter 238). I mean, I think I know what she means by “taller feet,” but the expression is so odd that I am not sure.

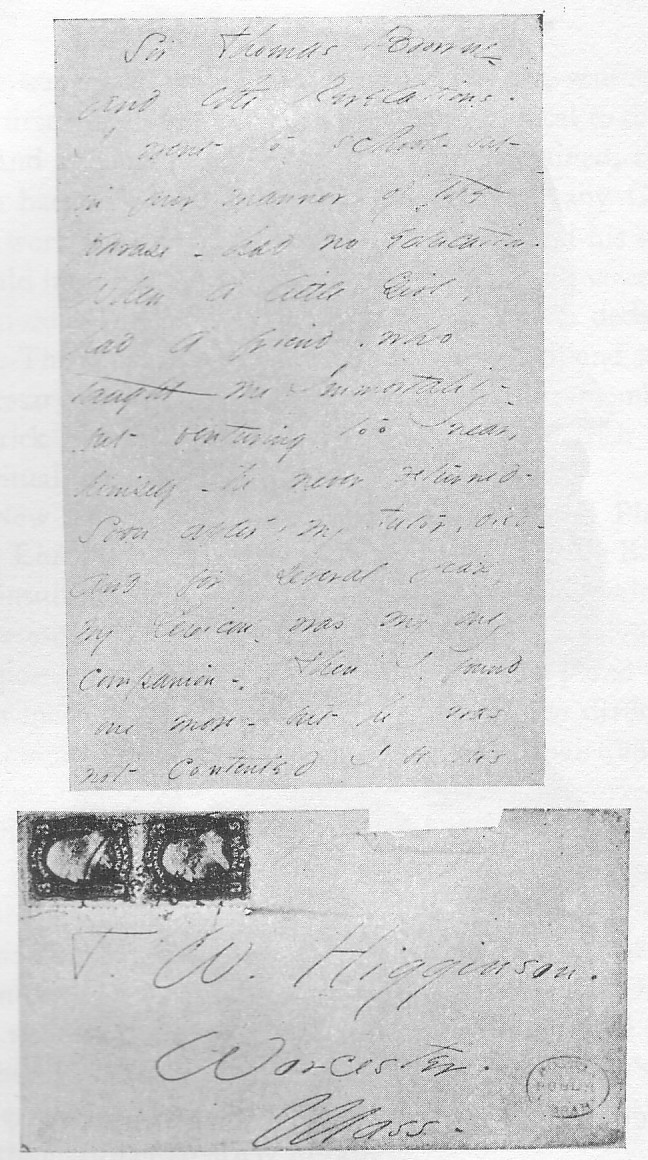

Her first letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, whom she wrote to out of the blue after he wrote an article of advice for writers for The Atlantic Monthly, includes similarly unusual diction:

Mr Higginson,

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself—it cannot see, distinctly—and I have none to ask—

Should you think it breathed—and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude—

If I make the mistake—that you dared to tell me—would give me sincerer honor—toward you—

I enclose my name—asking you, if you please—Sir—to tell me what is true?

That you will not betray me—it is needless to ask—since Honor is it’s [sic] own pawn— (Letter 260)

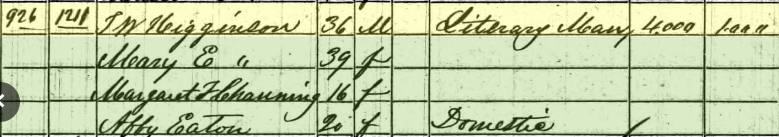

Dickinson sent that letter to Higginson while he lived in Worcester, MA, probably less than two miles from where I am sitting right now as I write this. Imagine receiving this letter from nowhere!

Dickinson could have chosen many words, but she asked if her “Verse is alive” (emphasis mine). Her second sentence is just a bold lie: she has plenty of people that she can and has asked to read her poetry and give her their opinions. She continues to play with the notion of “living” poetry through the wordplay of “breathed” and “quick” in the next sentence. Is she warning him not to publish her work in the final line? In any case, he didn’t know what he was looking at because he apparently told her she was not ready for publication. Her reply includes the deft line, “Thank you for the surgery—it was not so painful as I supposed” (Letter 261). She had to have been disappointed that he didn’t encourage her, but if so, she doesn’t betray it to anyone in her letters, and she didn’t seek to publish her work much in her lifetime, despite Helen Hunt Jackson’s encouragement.

In any case, it’s to Higginson’s credit that he recognized her genius enough before he died to edit several volumes of her poetry along with her brother’s mistress Mabel Loomis Todd. I do wish this collection had included Dickinson’s final letter to Higginson, from early May 1886 (the month she died):

Deity—does He live now?

My friend—does he breathe? (Letter 1045)

One of my instructors at the Emily Dickinson course suggests there is a circle closed with this final letter to Higginson. In her first letter to Higginson, she asks if her poetry is alive, if it breathes. Her final letter asks very similar questions. She had heard Higginson was sick and had to cancel a lecture he planned to give. The words are not accidental, not when you’re Emily Dickinson.

Perhaps most beautiful, and I dare you not to cry when you read it after reading this collection of letters, is the final letter Dickinson ever wrote. It is addressed to her Norcross cousins and reads simply:

Little Cousins,

Called back.

Emily (Letter 1046)

If you enjoy Dickinson’s poems, you will certainly delight in her letters.

I happen to have two copies of this collection, and it is a little bit hard to find nowadays. I’m not sure if it’s out of print, or what, but Amazon only sells it via third-party sellers. Stay tuned for a giveaway post since I do not need two copies.

This is probably the last book I’ll finish for the Backlist Reader Challenge, which means I fell pretty far short of finishing the challenge. However, this book has been on my TBR list since I first visited Emily Dickinson’s house.

This is probably the last book I’ll finish for the Backlist Reader Challenge, which means I fell pretty far short of finishing the challenge. However, this book has been on my TBR list since I first visited Emily Dickinson’s house.

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race by

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race by

Lee Daniel Kravetz’s

Lee Daniel Kravetz’s  About Lee Daniel Kravetz

About Lee Daniel Kravetz