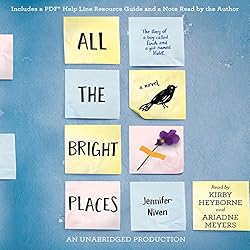

I decided that I would listen to All the Bright Places after I finished We Were Liars, which was also read by Ariadne Meyers. She’s a really good interpreter for YA.

I decided that I would listen to All the Bright Places after I finished We Were Liars, which was also read by Ariadne Meyers. She’s a really good interpreter for YA.

First all, if you read or listen to this book, be prepared to cry. Maybe especially if you listen to it, because Ariadne Meyers will make you cry at the end, and if she doesn’t, then Jennifer Niven will in her author’s note.

All the Bright Places is the story of Violet and Finch, who meet in the most improbable place: the bell tower at their high school. Both of them are contemplating suicide. Violet has sunk into depression after losing her sister in a car accident, while Finch’s problems are a bit more complicated—he has bipolar disorder, a disinterested family, an abusive father, and is bullied at school. Somehow, it’s not exactly clear who saves who, as the book’s description says, but soon they become friends and then something more as they work on a school assignment to explore the attractions of their home state of Indiana.

This is a great book, and the narration is particularly good. You are going to like it if you liked books like The Fault in Our Stars and Eleanor & Park. In fact, I’ve seen some reviews that insinuate that this book is a bit derivative of similar books that preceded it. First of all, I don’t think that’s the case. The stories all deal with similar themes, but ultimately, this book is Jennifer Niven’s story. I felt her characters were very real and recognizable in some ways that perhaps John Green’s aren’t. I feel his characters are often a bit too precocious and quirky, whereas I feel I have known teenagers who are more like Violet and Finch.

The narration is great, the story is great (give it a chance; the comparisons to other YA books are inevitable, but I really think this one stands on its own), and it’s not a topic that is dealt with a lot in YA. If you’re a teacher, get a copy for your classroom library; it will not be on your shelves very often.

Rating:

Audio Rating:

Some spoiler-y parts to follow, so fair warning. If you keep reading, it will help you understand how this book moved from four to five stars for me right at the end, but my assumption is that if you keep reading, then you are prepared to be spoiled because you either have already read this book and WANT TO TALK ABOUT THE FEELINGS or you don’t mind spoilers. You can still turn back if you are not sure.

Spoiler alert!

I had figured out that Theodore Finch was going to commit suicide well before he did. I mean, why else include the Help Line and Resource Guide, right? Plus, Finch is obsessed with suicide. He has researched the suicide methods of several famous people and recites them for the reader, and he actively tries to commit suicide at least once before he actually does. Then, he starts getting rid of his belongings and withdraws completely from everyone, even Violet. So I wasn’t surprised when he did it, and my eyes stayed pretty dry until the end when Ariadne Meyers read the last chapters when Violet found the note that Finch left her in one of the places they had planned to visit. Still, just a few sniffles really because, you know, fiction. I know, I know. I can bawl my eyes out knowing Catherine is going to die at the end of A Farewell to Arms (a book from which, aptly, Niven draws a line for her introduction), and I can’t shed a tear for Theodore Finch? Well, like Violet, I guess I was mad at him for not getting help (even though I knew he wouldn’t). I was furious with his parents for not caring enough for him to notice he was in real trouble. I don’t really know how I felt. However, Jennifer Niven explained that this book came from her own story in her author’s note. Her great-grandfather committed suicide, which was an event that left ripples through her family even to the present day.

The same thing happened in my family. My great-grandfather, Omar Gearhart, committed suicide on December 29, 1930. He had been battling some major problems, and I’m not clear what they were, except that later, my grandfather described his father as “crazy,” and his younger brother recalled hiding under the porch from my great-grandfather. There is a lot that I do not know. I know some of his children were taken away from the family and were adopted by other families before he died. I know that my grandfather was one of them. I know also that the children were told their father was murdered, which is something my grandfather’s sisters both confirmed. I guess somehow their mother thought it would be easier to hear, though I confess I’m not sure why, because then the children grew up thinking that their father had been murdered and nothing was ever done about it. I didn’t think that sounded right. More and more, I wondered if the official story was true, so I sent away for my great-grandfather’s death certificate—a matter of public record. And it said he died of a gunshot wound to the head, self-inflicted. Contributing cause was “despondency.” And still, to this day, I had family members whose first reaction when I told them was shame and secrecy.

People, shame and secrecy is not how we prevent suicide. It’s how we perpetuate the problem. We say that having a mental illness is something to be embarrassed about, hidden. Finch says, “Labels like ‘bipolar’ say This is why you are the way you are. This is who you are. They explain people away as illnesses.” He, too, is reluctant to connect himself with this label. Even though I didn’t know the truth about my great-grandfather until recently, his death did ripple across the generations.

Niven also shares the other personal connection she had to this story: she loved a boy when she was a teenager, and that boy committed suicide. And Jennifer found him. How devastating. I think, but I’m not sure, that my great-grandmother found my great-grandfather. My dad says he remembers her. He remembers visiting her. He told me that even when she smiled, she seemed sad. She lost several of her children for reasons I will probably never know, though she was allowed to visit them, and she lost her husband. She had a very sad life. And she was beautiful.

So, I don’t know, that personal connection somehow added a star to the book. I think books are sometimes mirrors for us, and I could see my own story in that book, in some way.

Spoiler over.

I just finished listening to this book as well and thought Niven did a remarkable job creating believable teenage characters and illustrating such an isolating, internal process. Moving between the first-person narration of Violent and Finch was especially effective in being able to see how a person struggling with mental illness views him/herself even as an outside may see that person so differently.

Thanks for sharing your personal connection with this book through this review. I enjoyed reading it so closely after finishing the book myself.

Thank you!