The Arctic Fury by Greer Macallister

The Arctic Fury by Greer Macallister Published by Sourcebooks Landmark on December 1, 2020

Genres: Historical Fiction, Mystery

Pages: 300

Format: E-Book

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

In early 1853, experienced California Trail guide Virginia Reeve is summoned to Boston by a mysterious benefactor who offers her a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity: lead a party of 12 women into the wild, hazardous Arctic to search for the lost Franklin Expedition. It’s an extraordinary request, but the party is made up of extraordinary women. Each brings her own strengths and skills to the expedition- and her own unsettling secrets. A year and a half later, back in Boston, Virginia is on trial when not all of the women return. Told in alternating timelines that follow both the sensational murder trial in Boston and the dangerous, deadly progress of the women’s expedition into the frozen North, this heart-pounding story will hold readers rapt as a chorus of voices answer the trial’s all-consuming question: what happened out there on the ice?

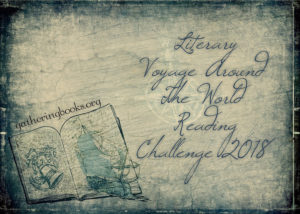

My first book of 2021! I probably wouldn’t have picked up this book if not for the Book Voyage: Read Around the World Challenge. Before I share some thoughts about the book, I’d like to thank the challenge hosts for two things: 1) offering a list of recommended books for each region in the challenge, and 2) recommending this particular book, which brought me out of a reading funk and kept me up late wanting to find out what would happen next. I love participating in challenges, but I find it difficult sometimes because I don’t know what to read for the challenge, and it is refreshing to have a list of books to consider at least. I probably wouldn’t have heard about The Arctic Fury if not for this challenge, either, or at least I wouldn’t have heard of it for some months.

This book is just the kind of historical fiction I love. It puts women at the forefront of a plausible, well-researched story. I admit I struggled a bit with the notion that Lady Franklin would sink her hopes into an all-female expedition to the Arctic in search of her missing husband, but I was willing to go with the premise. However, without spoiling the ending, I’ll just say that Lady Franklin’s actions make much more sense by the end, and I wound up finding the premise more plausible.

If this book suffers from anything, it’s a little bit of a kitchen-sink approach—the author tackled just about every aspect of being a woman in the 1850s, from race to gender to pregnancy to sexuality to limited options to the threat of violence from men. Some of the aspects included didn’t feel strictly necessary to the story but rather an effort to be inclusive. I appreciated this about the book, but I think including the spectrum of experiences should be purposeful, and it didn’t always strike me that way in this book. Some pretty serious liberties were also taken with the protagonist’s (a known historical figure) story. Even though I understood the rationale for doing so, it bothered me, and I think the only other solution would have been to invent a person who didn’t actually exist to have a similar past. Once I figured out who she really was, I was able to find out what happened to her after what she calls the Very Bad Thing after about a minute’s search.

However, the other aspects of the novel are well-researched and feel authentic, which Macallister attributes to ensuring that “each woman [on the journey] had a real-life counterpart, an inspiration from the mid-nineteenth century [she] could point to and draw from” (401). As a result, each woman was believable. I particularly appreciated that the women each had their own strengths and flaws. They seemed much more human for being well-rounded. Each woman was also given at least one chapter in her own voice, which gave them even more depth and humanity.

I also appreciated the way the story alternated between Virginia’s murder trial and the voyage in the Arctic. The alternating timelines added more suspense to the story. I actually tagged this as a mystery in addition to historical fiction, even though it’s not a traditional mystery per sé. Like some of the best mysteries, neither what truly happened nor how it will all turn out was revealed until the climactic ending.

Bottom line: I definitely recommend this one to anyone who likes historical fiction, particularly with strong women characters. The Arctic Fury is well-written and researched, but most of all, the characters are memorable, intriguing, and real.

She Lies in Wait by

She Lies in Wait by

Americanah by

Americanah by

For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World's Favorite Drink and Changed History by

For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World's Favorite Drink and Changed History by

The Movement of Stars by

The Movement of Stars by

The Complete Sherlock Holmes by

The Complete Sherlock Holmes by

The Miniaturist by

The Miniaturist by

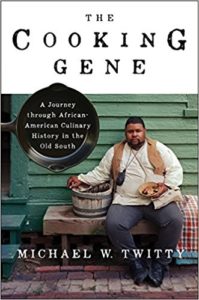

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by