Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward Published by Scribner on May 8, 2018

Genres: Contemporary Fiction

Pages: 320

Format: Paperback

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

An intimate portrait of a family and an epic tale of hope and struggle, Sing, Unburied, Sing examines the ugly truths at the heart of the American story and the power—and limitations—of family bonds.

Jojo is thirteen years old and trying to understand what it means to be a man. His mother, Leonie, is in constant conflict with herself and those around her. She is black and her children’s father is white. Embattled in ways that reflect the brutal reality of her circumstances, she wants to be a better mother, but can’t put her children above her own needs, especially her drug use.

When the children’s father is released from prison, Leonie packs her kids and a friend into her car and drives north to the heart of Mississippi and Parchman Farm, the State Penitentiary. At Parchman, there is another boy, the ghost of a dead inmate who carries all of the ugly history of the South with him in his wandering. He too has something to teach Jojo about fathers and sons, about legacies, about violence, about love.

Rich with Ward’s distinctive, lyrical language, Sing, Unburied, Sing brings the archetypal road novel into rural twenty-first century America. It is a majestic new work from an extraordinary and singular author.

I think everyone has been recommending this book to me. It’s been on my TBR list for a while. Sing, Unburied, Sing is drawing comparisons to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, which Ward acknowledges she was “thinking about” when she wrote, in addition to Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Odyssey, though she didn’t re-read any of these books as part of her process. Rather, she turned to histories of Mississippi, particularly of Parchman Farm, now known as the Mississippi State Penitentiary.

Jojo and his mother Leonie narrate most of the book. Jojo is easy to empathize with: he’s known such suffering, and he will know more, but he also is capable of great love. It would be easy to reject Leonie entirely, given her abusive parenting and drug addiction, but Ward doesn’t let the reader off the hook so easily. She shows us Leonie’s pain and humanity, too, and even if we can’t forgive her, like we know Jojo will also not be able to do, we can’t dismiss her entirely, either.

The imagery at the end of this book will stay with me for a long time. When Jesmyn Ward places herself as part of a “long line” and says she feels “like all of those writers—from William Faulkner, to Richard Wright, to Eudora Welty, to Margaret Walker,” insisting that these writers have “affected [her] writing,” one can hardly argue (interview excerpts in paperback edition). She evokes the same Mississippi, from the Delta to the clay to the ghosts. Ward centers those stories in our present day, but her novel is also tethered to the past and explores the ways in which we are our histories, our present, and our future all wrapped in one.

In trying to put language to my thoughts, I found myself reading Tracy K. Smith’s review in The New York Times, and she captures my thoughts so well:

Maybe that’s the miracle here: that ordinary people whose lives have become so easy to classify into categories like rural poor, drug-dependent, products of the criminal justice system, possess the weight and the value of the mythic—and not only after death; that 13-year-olds like Jojo might be worthy of our rapt attention while their lives are just beginning.

That’s the magic of this book. Characters that many readers might be tempted to dismiss as unworthy of our attention become mythically important. At the same time, the characters are very real. I feel like I have known them, especially as I lived in the South and have Southern roots. Faulkner famously said once that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Nowhere else does that claim feel truer to me than in the South, even though the area of the country where I live now has more “history,” if one measures in the number of years since it’s been colonized. There is a passage from the viewpoint of Richie, the ghost of a boy who died at Parchman Farm, that captures the way history seems to hang onto the land in the South and also captures something of the lyricism of Ward’s writing:

I didn’t understand time, either, when I was young. How could I know that after I died, Parchman would pull me into it and refuse to let go? And how could I conceive that Parchman was past, present, and future all at once? That the history and sentiment that carved the place out of the wilderness would show me that time is a vast ocean, and that everything is happening at once?

I was trapped, as trapped as I’d been in the room of the pines where I woke up… Parchman had imprisoned me again. I wandered the new prison night after night. It was a place bound by cinder blocks and cement… I spent so many turns of the earth at the new Parchman… I despaired, burrowed into the dirt, slept, and rose to witness the newborn Parchman. I watched chained men clear the land and lay the first logs for the first barracks for gunmen and trusty shooters. I thought I was in a bad dream. I thought that if I burrowed and slept and woke again, I would be back in the new Parchman, but instead, when I slept and woke, I was in the Delta before the prison, and Native men were ranging over that rich earth, hunting and taking breaks to play stickball and smoke. Bewildered, I burrowed and slept and woke to the new Parchman again, to men who wore their hair long and braided to the scalps, who sat for hours in small windowless rooms, staring at big black boxes that streamed dreams. Their faces in the blue light were stiff as corpses. I burrowed and slept and woke many times before I realized this was the nature of time. (186-187)

If you hover over the Mississippi State Penitentiary, previously known as Parchman Farm, in Google Maps, you can’t help but notice how blighted the landscape looks. I am especially struck by the roundness of the landscape. It definitely looks like it holds history.

Here’s a classic song about Parchman Farm, one of my favorite old Delta blues songs, by Bukka White.

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by  U2 by U2 by

U2 by U2 by  The Sympathizer by

The Sympathizer by

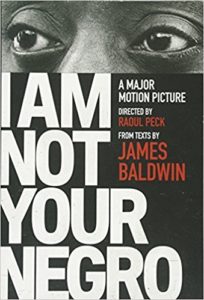

I Am Not Your Negro by

I Am Not Your Negro by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by