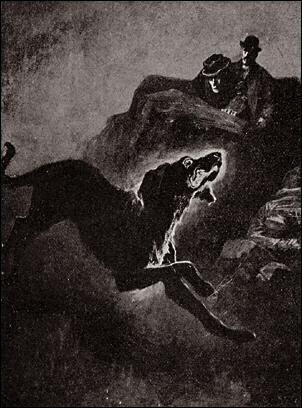

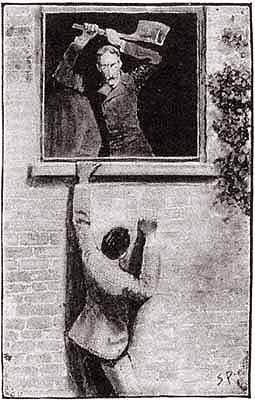

The Hound of the Baskervilles is the fourth and final novel in the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It’s one of the most memorable stories in the Sherlock Holmes canon, and as such, is one of the most frequently adapted stories. Dr. James Mortimer consults Sherlock Holmes regarding the mysterious case of a legendary curse on the Baskerville family. Sir Charles Baskerville has recently died under suspicious circumstances, and his heir and nephew will soon arrive from Canada to claim his inheritance. Dr. Mortimer hopes young Henry Baskerville will not also inherit the Baskerville family curse. Holmes agrees to take the case, but even before Henry Baskerville leaves London for his Devonshire estate, strange things happen. Someone seems to be following him, and one of his shoes turns up missing. Holmes sends Watson on to Baskerville Hall with Henry Baskerville and asks Watson to keep him updated regarding events until he can extricate himself from a case. Watson soon discovers that there may be some truth the family legend of a vicious dog that hunts Baskervilles, and he also discovers the dog may not be the only mysterious being hiding on the moor.

This story is easily one of Conan Doyle’s best Sherlock Holmes mysteries. It has everything that Conan Doyle does well, including an atmospheric setting, suspense and mystery, and a hint of the supernatural. It also refrains from including some of the things Conan Doyle doesn’t do as well, such as exotic settings (India, America). Conan Doyle plants enough clues that many astute readers will begin to suspect the truth behind the mystery, but not so many that it feels obvious to everyone. It’s easily the best of Conan Doyle’s four Sherlock Holmes novels, and it ranks among the best of his Sherlock Holmes stories in general for this reader. The setting of Baskerville Hall and the surrounding moor is captured well, and it perhaps the setting that is most remembered about this story.

The BBC series Sherlock adapted this story in the episode “The Hounds of Baskerville.” In this modern adaptation, Sherlock and Watson take on a case at Baskerville, a military research facility. Henry Knight claims his father was killed by a gigantic hound on the moor, but it turns out that the hounds are images produced as the result of mind-altering drugs, and H.O.U.N.D. was a secret government project adapting the drugs as chemical weapons. Because this story is one of the most popular Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock creator Mark Gatiss has said he felt he needed to be more careful to keep the most well-known aspects of the story intact. The story is, however, updated to reflect modern concerns.

Rating:

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the twenty-sixth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Blue Carbuncle.”

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the twenty-sixth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Blue Carbuncle.”

Lee Daniel Kravetz’s

Lee Daniel Kravetz’s  About Lee Daniel Kravetz

About Lee Daniel Kravetz