Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout Published by Random House Trade on September 30th 2008

Pages: 286

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

At times stern, at other times patient, at times perceptive, at other times in sad denial, Olive Kitteridge, a retired schoolteacher, deplores the changes in her little town of Crosby, Maine, and in the world at large, but she doesn’t always recognize the changes in those around her: a lounge musician haunted by a past romance; a former student who has lost the will to live; Olive’s own adult child, who feels tyrannized by her irrational sensitivities; and her husband, Henry, who finds his loyalty to his marriage both a blessing and a curse.

As the townspeople grapple with their problems, mild and dire, Olive is brought to a deeper understanding of herself and her life—sometimes painfully, but always with ruthless honesty. Olive Kitteridge offers profound insights into the human condition—its conflicts, its tragedies and joys, and the endurance it requires.

I can’t remember anymore why I decided to read Olive Kitteridge. I had it in my head somehow that I wouldn’t like it. I do think it’s a bit uneven in that the stories that don’t feature Olive herself seem tangential. In a few cases, Olive is mentioned in a way that seems forced as though Strout was attempting to tie together stories that weren’t tied together. She explains this in the interview in the back: “I chose this form primarily because I envisioned the power of Olive’s character as best told in an episodic manner. I thought the reader might need a little break from her at times, as well” (276). The episodic manner works very well for revealing Olive’s character, as Strout suspected it would.

The best stories told from an alternative point of view are “Pharmacy,” told from Henry Kitteridge’s point of view and “Incoming Tide,” told from Olive’s former student Kevin Coulson’s point of view. The other stories were fine, but in terms of belonging in a collection of stories about Olive, they didn’t quite fit for me. Olive was easily the most intriguing character in the book. It was her personality—at once completely recognizable and by turns compelling and repellent—that kept me turning the pages in this book.

We all know an Olive. She’s hard to like, but I quibble when she’s described as “abrasive.” If she were a man, I’d lay odds that’s not a word anyone would use to describe her. That adjective seems to be applied almost universally to women, who are supposed to be nice and are supposed to be easy to like. Olive would not approve of my saying this, but fuck that. It’s more important to have character. For example, in “A Little Burst,” when Olive draws on her new daughter-in-law’s sweater and steals one of her shoes and a bra after hearing the young woman make fun of the dress Olive had worn to the wedding, all I could think was good for Olive. No, I wouldn’t have liked it if my mother-in-law had done that to me, but I also wouldn’t have been mocking my mother-in-law behind her back at my wedding. Christopher, Olive’s son, seems to have a great deal of difficulty with his mother, and she might not see her parenting in the most accurate light, but he’s a difficult son as well. Henry, the character who suffers most from Olive’s personality, emerges as genuine and caring, and his fate is perhaps most tragic.

Of the stories in the collection, my favorites were “A Little Burst”—which reminds me in the best way of Flannery O’Connor’s writing—and “River,” the final story in the collection. There were moments when I put this book down for a long period of time, but I picked it up thinking I’d like to cross one more unfinished book off my list before the end of the year. Truthfully, the moments when I put the book down were the times when Olive was offstage. She drives the entire book, and I enjoyed the ride very much when she was behind the wheel.

I lied. I thought Emily Dickinson: Selected Letters would be the last book I’d finish for the Backlist Reader Challenge. Olive Kitteridge probably is.

I lied. I thought Emily Dickinson: Selected Letters would be the last book I’d finish for the Backlist Reader Challenge. Olive Kitteridge probably is.

Selected Letters by

Selected Letters by

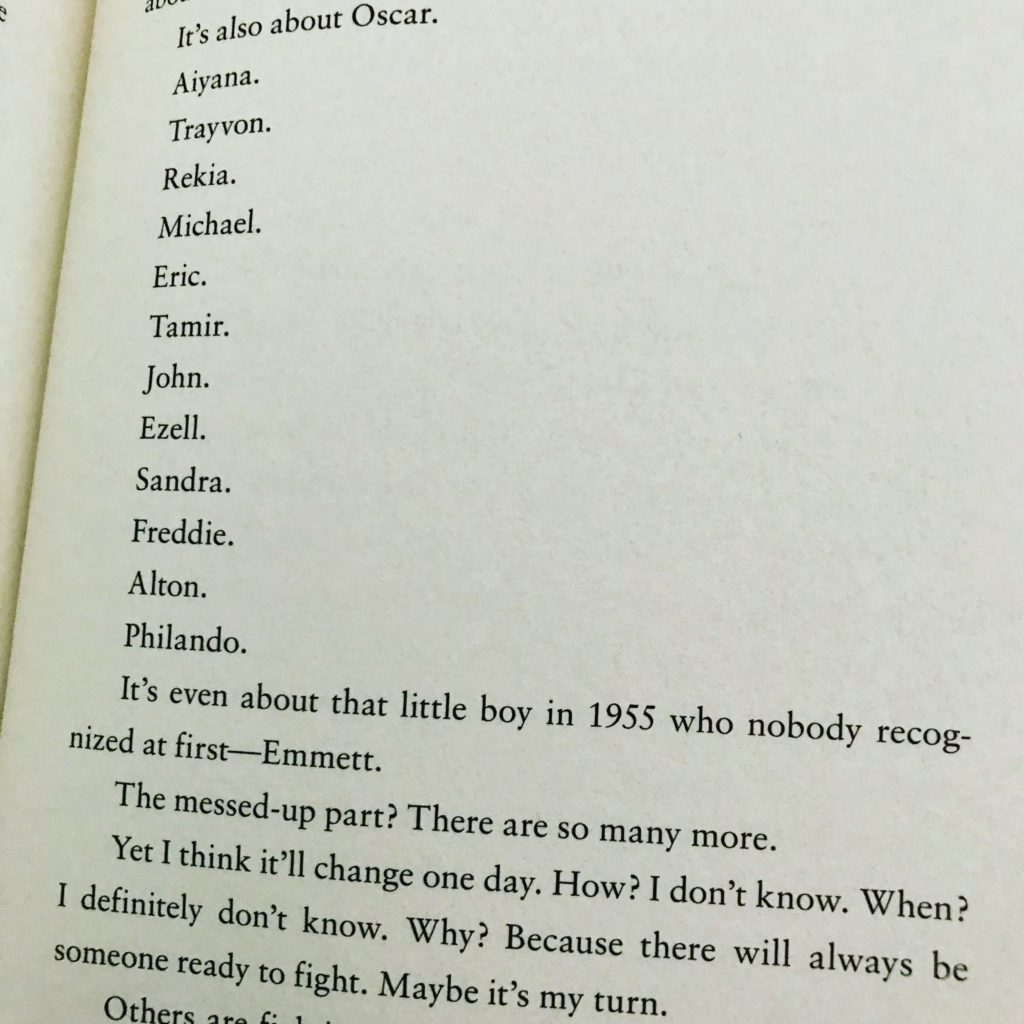

How It Went Down by

How It Went Down by

1984 by

1984 by  The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race by

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race by  Long Way Down by

Long Way Down by  Tess of the D'Urbervilles by

Tess of the D'Urbervilles by