I have not reviewed cookbooks on this blog before, though I have been collecting cookbooks for a few years, and I have some really good ones that I should share with you all.

Cooking is not really something I have a ton of time to do, but I actually do like cooking. I am a very slow cook, and I make a great big mess when I cook, but I enjoy the process.

Bread, however, is something I have always shied away from, especially after some failed attempts. I tried to make a pie crust for my pumpkin pie and failed. I made a white bread recipe from the Better Homes and Gardens cookbook, and it was okay, but certainly nothing to write home about. The only bread successes (discounting breads like zucchini bread and pumpkin bread, which didn’t use yeast and did not need to be kneaded) were my Thanksgiving dinner rolls. I credit the really excellent instructions for that success.

Everyone knows bread is picky. You have to knead it just right or else it will not turn out well. You have to have to fuss with the yeast, and everyone knows how finicky yeast is about how it’s handled. So, like many people, I was always a bit afraid to experiment with bread. A few weeks ago, that changed when I found Alexandra Stafford’s mother’s famous peasant bread recipe at her blog Alexandra Cooks. I read over the recipe. I watched one of the videos. It didn’t look hard. So I tried it with all wheat flour, not knowing (because I am not a bread baker) that I was going to get a denser loaf of bread. But you know what? It was still amazing. I couldn’t believe how easy it was. I hit on Alexandra’s advice to keep the flour weight at 512 grams, and the next time I made bread, I used about two cups of wheat flour and made the rest of the weight up with unbleached white flour. It was perfect. Measuring by weight was the trick. The consistency was just like Alexandra’s pictures, and the bread was not too dense. That’s how easy the recipe is. No kneading. The time you spend actually fussing with the bread is maybe five minutes. The rest of the time is just letting it rise. It’s a very forgiving recipe in that even if you mess up on a step, it still seems to turn out just fine.

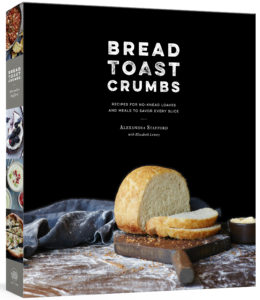

My family loved the bread, too. The recipe makes two loaves, and twice, I’ve come into the kitchen to find my son has taken half a loaf before I could even cut it. I knew I wanted to try the variations on the recipe in Alexandra’s book Bread Toast Crumbs: Recipes for No-Knead Loaves and Meals to Savor Every Slice. I have read through the book, though I haven’t made many of the recipes yet. The recipes are straightforward and easy to follow. Alexandra offers some tricks and advice for those of us who don’t often bake (for example, toast nuts before using them in breads—this is a trick I had picked up from a friend of mine at work, but it was nice to see it validated in the book). The book has many variations on the peasant bread recipe in the Bread section. In the Toast section, Alexandra shares recipes for spreads, jams, soups, sandwiches, entrées, and desserts that use the various bread recipes. In the Crumbs section, she shares salads, soups, side dishes, pasta, entrées, and desserts that use crumbs made from the various breads. Each section has its own introduction with more tips.

The photography in the book (like most cookbooks) is beautiful and serves as a nice guideline for bakers. I can’t wait to try more of the recipes. I’m especially eyeing the Roasted Garlic Bread. Today, I tried out the Oatmeal-Maple bread on p. 41. Here are some pictures of one of the loaves I made today. It’s already been eaten, by the way.

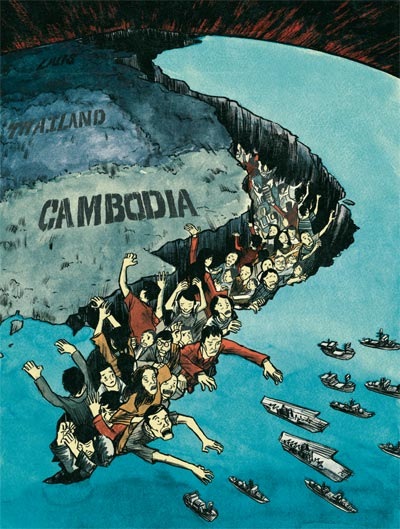

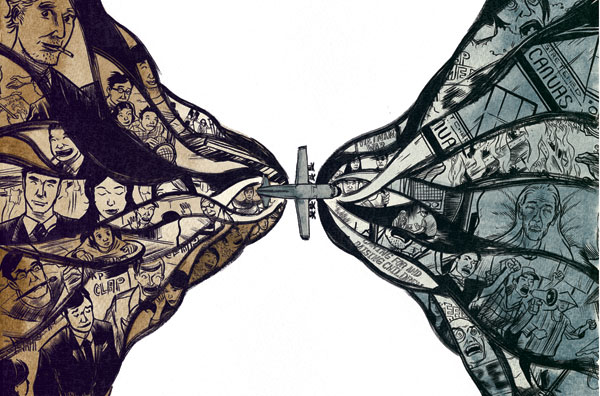

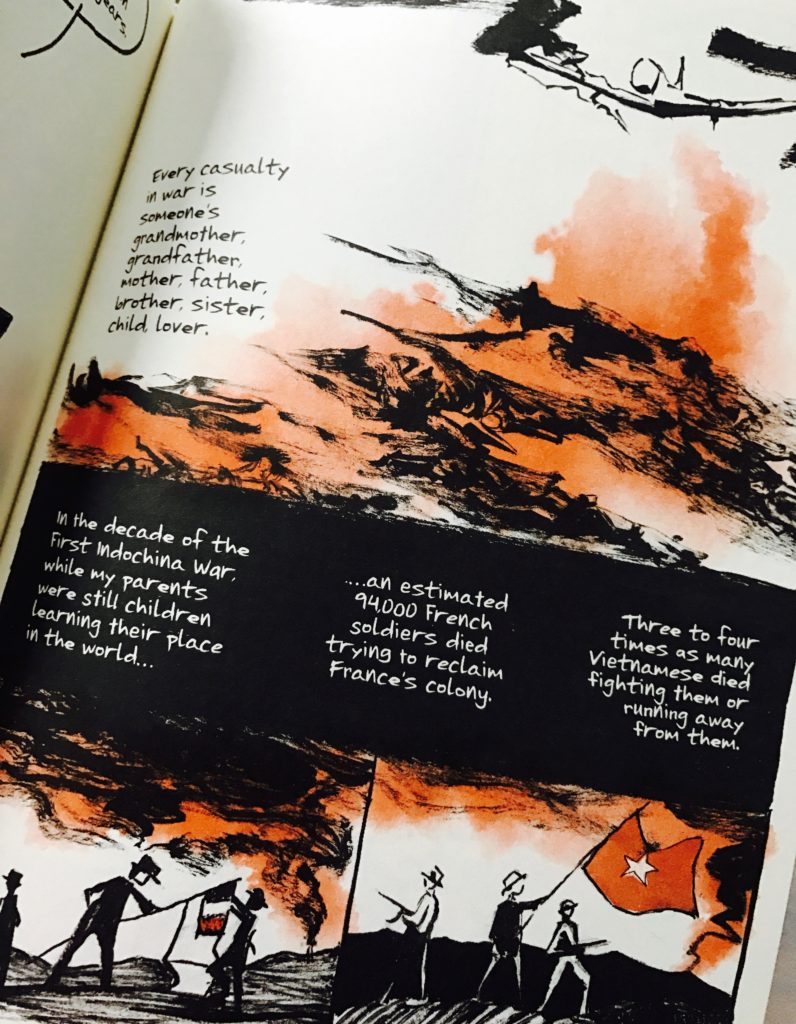

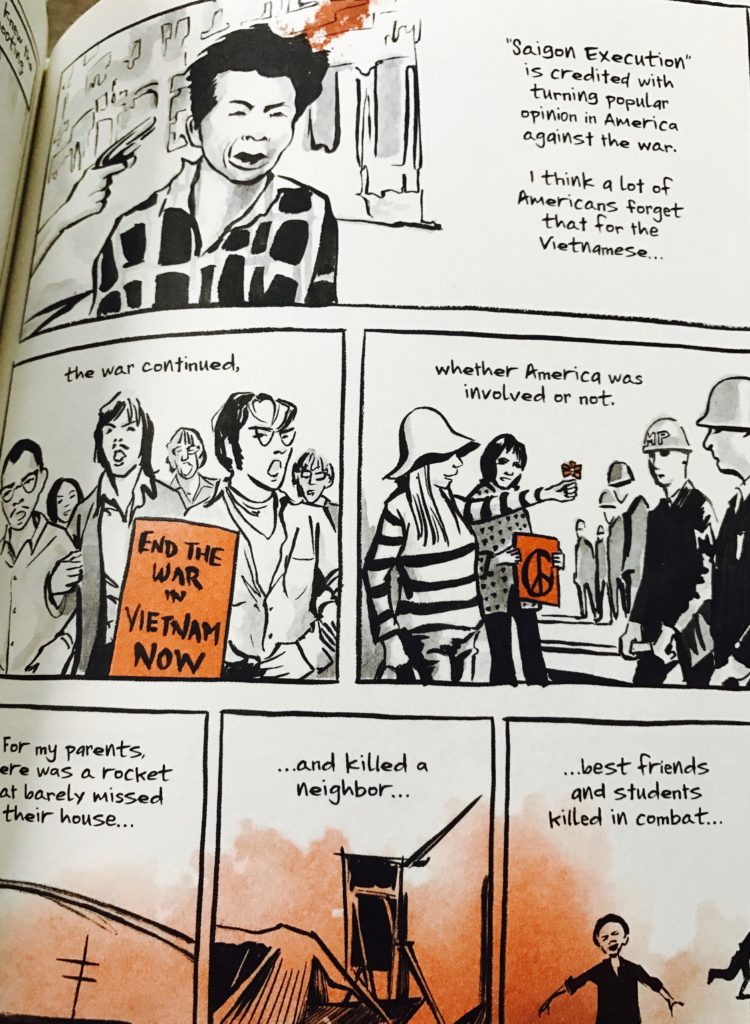

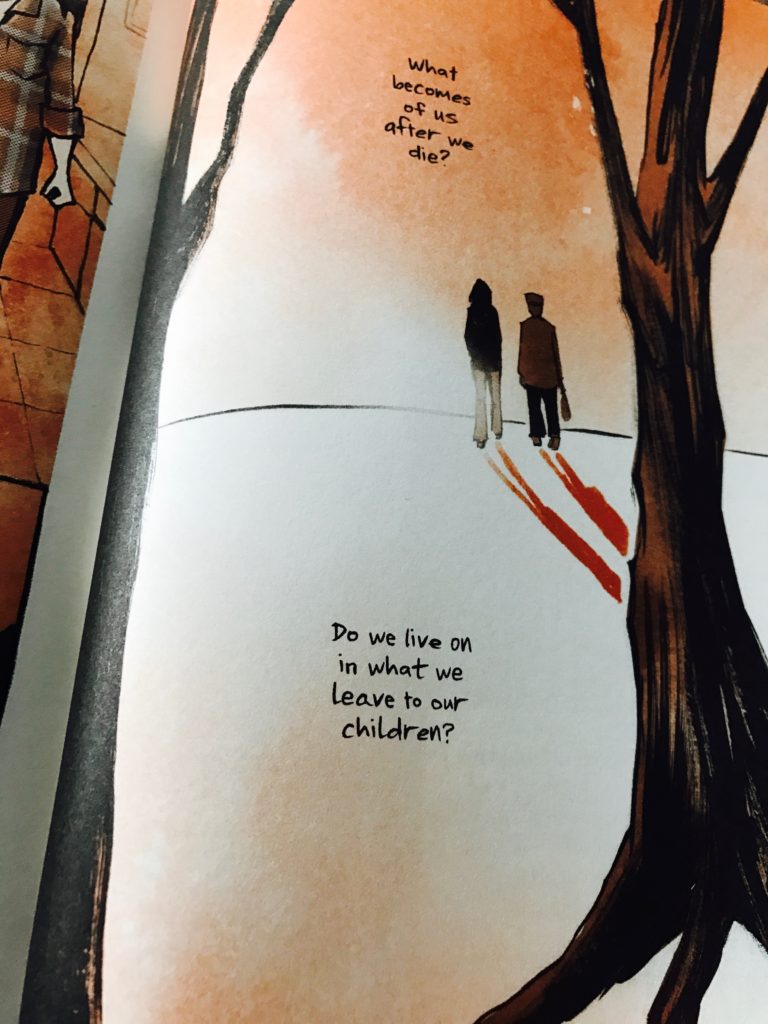

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.