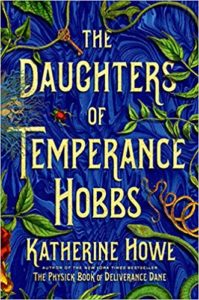

The Daughters of Temperance Hobbs by Katherine Howe

The Daughters of Temperance Hobbs by Katherine Howe Published by Henry Holt and Co. on June 25, 2019

Genres: Historical Fiction, Fantasy/Science Fiction

Pages: 352

Format: Hardcover

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

New York Times bestselling author Katherine Howe returns to the world of The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane with a bewitching story of a New England history professor who must race against time to free her family from a curseConnie Goodwin is an expert on America’s fractured past with witchcraft. A young, tenure-track professor in Boston, she’s earned career success by studying the history of magic in colonial America—especially women’s home recipes and medicines—and by exposing society's threats against women fluent in those skills. But beyond her studies, Connie harbors a secret: She is the direct descendant of a woman tried as a witch in Salem, an ancestor whose abilities were far more magical than the historical record shows.

When a hint from her mother and clues from her research lead Connie to the shocking realization that her partner’s life is in danger, she must race to solve the mystery behind a hundreds’-years-long deadly curse.

Flashing back through American history to the lives of certain supernaturally gifted women, The Daughters of Temperance Hobbs affectingly reveals not only the special bond that unites one particular matriarchal line, but also explores the many challenges to women’s survival across the decades—and the risks some women are forced to take to protect what they love most.

I happened upon The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane in a bookstore shortly after it was first published and snatched it up immediately. Salem? Witches? Academia? Right up my alley for sure. As soon as I found out its followup, The Daughters of Temperance Hobbs was coming out, I preordered it, which is something I rarely do. You do not have to have read The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane in order to enjoy its followup, but I think you will enjoy it more if you do. In fact, after finishing The Daughters of Temperance Hobbs, I want to go back and read The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane again.

This book offers a bit more of Deliverance’s backstory, but mainly focuses on her descendants Connie, as Physick Book did, and Temperance (also Connie’s ancestor). Readers are also treated to peeks inside the lives of each generation of the family going back to Deliverance’s parents in England. I had to go back and make a family tree for myself, but it’s a bit spoilery, so I’ll put it at the end for those of you who want to read the book first.

Just as I did with Physick Book, I connected personally in many ways with this book. Just like Connie, I called my own grandmother Granna, and I thought I’d invented the name. When I told Katherine Howe this story years ago, she said she thought she had made it up, too! Prudence’s diary reminds me a great deal of my own ancestor Stella Bowling Cunningham’s diary, and Katherine Howe shared she had been inspired by Prudence Ballard’s A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812. This book has some other interesting connections. Connie is working on obtaining tenure as a history professor at Northeastern University, where I am currently pursuing a doctorate in education.

This next bit is maybe the tiniest bit of a spoiler, but I don’t think knowing it in advance hurts anyone’s enjoyment, so I’ll spill. There is a sort of interesting parallel for me in that Connie considers applying for a position at Harvard, but realizes it would not work for her. I actually applied to Harvard’s Graduate School of Education doctoral program. I didn’t get in (it’s at least as selective as undergraduate admissions, though I hear getting into their master’s program is pretty easy—but I already have a master’s and didn’t want to work on another one, even at Harvard). I was really bummed out about it, but I had a conversation with a friend of Steve’s, who made me feel better about the rejection and also encouraged me to apply to another program. I applied to the program at Northeastern. I was really attracted to it in the first place when I was making a list of graduate schools to apply to, but I think I was charmed by the idea of attending Harvard, just like Connie is initially charmed by the idea of the assistant professor job at Harvard, even though she knows it will not lead to tenure, and the job at Northeastern will. It’s so weird! I know now that the program at Northeastern is much more suited to what I want to do, where I am in my professional life right now, and the goals I have for the future. Just like Connie. I know it’s a minor similarity, but I connected to it.

One of the things I like about Katherine Howe’s writing is her eye for the tiny detail—the way someone leans against a countertop or plays with their hair—it brings her characters to life. I feel like I can really see everything she is describing. Her characters are also interesting and likable. I really liked Connie’s protege Zazi Molina. Temperance herself is an awesome character as well. As in Physick Book, the book’s settings themselves, from the old house on Milk Street in Marblehead, to Connie’s apartment on Mass Ave. in Cambridge, to the probate office in Salem, all the settings come alive. This is a fun and engaging read, but you’ll also learn something about history into the bargain.

Here is the family tree if you want it. Mild spoilers.

Deliverance Hasseltine Dane (parents are Robert and Anne Hasseltine)

+Mercy Dane Lamson

++Prudence Lamson Bartlett

+++Patience Bartlett Jacobs

++++Temperance Jacobs Hobbs

+++++Faith Hobbs Bishop

++++++Verity Bishop Lawrence

+++++++Chastity Lawrence

++++++++Charity Lawrence Crowninshield

+++++++++Sophia Crowninshield Goodwin

++++++++++Grace Goodwin

+++++++++++Constance “Connie” Goodwin

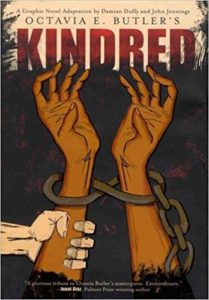

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by

Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly by

Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly by

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by  Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by

Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by  Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by

There There by

There There by

Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People by

Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People by  Homegoing by

Homegoing by