Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers by Eric Pallant

Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers by Eric Pallant Published by Agate Surrey on September 14, 2021

Genres: Cooking, History, Nonfiction

Pages: 280

Format: Hardcover

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Sourdough bread fueled the labor that built the Egyptian pyramids. The Roman Empire distributed free sourdough loaves to its citizens to maintain political stability. More recently, amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, sourdough bread baking became a global phenomenon as people contended with being confined to their homes and sought distractions from their fear, uncertainty, and grief. In Sourdough Culture, environmental science professor Eric Pallant shows how throughout history, sourdough bread baking has always been about survival.

Sourdough Culture presents the history and rudimentary science of sourdough bread baking from its discovery more than six thousand years ago to its still-recent displacement by the innovation of dough-mixing machines and fast-acting yeast. Pallant traces the tradition of sourdough across continents, from its origins in the Middle East's Fertile Crescent to Europe and then around the world. Pallant also explains how sourdough fed some of history's most significant figures, such as Plato, Pliny the Elder, Louis Pasteur, Marie Antoinette, Martin Luther, and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, and introduces the lesser-known—but equally important—individuals who relied on sourdough bread for sustenance: ancient Roman bakers, medieval housewives, Gold Rush miners, and the many, many others who have produced daily sourdough bread in anonymity.

Each chapter of Sourdough Culture is accompanied by a selection from Pallant's own favorite recipes, which span millennia and traverse continents, and highlight an array of approaches, traditions, and methods to sourdough bread baking. Sourdough Culture is a rich, informative, engaging read, especially for bakers—whether skilled or just beginners. More importantly, it tells the important and dynamic story of the bread that has fed the world.

I bought this book for myself as a birthday present. I learned some interesting things about how sourdough culture works as well as its use in historical bread baking. Pallant begins his history of sourdough with the conceit of tracing the origin of his own sourdough starter. He was told that its provenance was in the mining town of Cripple Creek, CO. in 1893; however, proving it turns out to be an impossible task. Pallant makes a case that sourdough’s survival is miraculous in the age of commercial yeast. He also addresses the boom in home-baked sourdough in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. (I personally know several people who never baked sourdough before the pandemic, and now they’re more expert than I am! Disclosure: I am not an expert.)

The historical aspects of the book are certainly interesting, though, at times, Pallant veers off-topic a bit. I found the scientific discussion of yeasts and bacteria really fascinating. Honestly, one of the first things I wanted to do was have my sourdough starter tested to see what sorts of yeasts and bacteria it contains. Can one do this? I feel like I found a website for a place where you could send your starter for testing, but now that I’m trying to find it again, I wonder if I dreamed it—sort of a 23 and Me for sourdough starter. I wouldn’t expect to find anything particularly odd about my starter, but it would be interesting to see what the dominant strains of yeast and bacteria are.

I found the chapter about the mass production of bread to be interesting, mainly because it helps explain why home-baked bread, even bread made with commercial yeast, tastes so much better than mass-produced bread. Honestly, his description of the Chorleywood Bread Process that is used to make commercial bread is kind of gross. It definitely did not make me want to go back to commercial bread, though, to be fair, I’m not sure if that process is used in the USA.

Pallant understands that making bread connects us to humanity’s history. I always feel connected to the past when I make a loaf of bread, and I feel even more connected when I make a loaf of sourdough. Sourdough demands time and patience, both of which are hard to come by in the 21st century.

Pallant also includes quite a few recipes, but frankly, there isn’t much that’s new. One recipe, for example, is Chad Robertson’s sourdough recipe. If you are looking for recipes, you’d do better to buy a bread recipe book. In fact, buy Chad Robertson’s Tartine Bread. Because Pallant spoke so highly of it, I bought Daniel Leader’s Living Bread: Tradition and Innovation in Artisan Bread Making (paid link), and I’m looking forward to reading that book and trying some of the recipes.

I would probably recommend this book only to true bread freaks. I’m not sure people who don’t bake would enjoy it. On the other hand, if you are interested in food history or microhistory (history focusing on a narrow subject), then you might still enjoy this book even if you don’t bake.

Tartine Bread by

Tartine Bread by

My Bread: The Revolutionary No-Work, No-Knead Method by

My Bread: The Revolutionary No-Work, No-Knead Method by

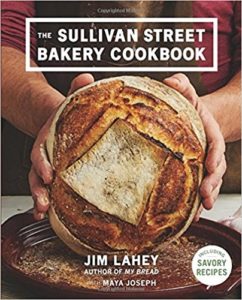

The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook by

The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook by