Jerome Charyn recently gave a lecture at the Frost Library at Amherst College, which I attended and wrote about on this blog. I wanted to start reading the book right after the talk, but I believe I was in the middle of The Club Dumas, which took me forever to finish (because I didn’t like it and should have given up on it). I wanted to finish The Club Dumas before reading A Loaded Gun. After a while, I sort of used A Loaded Gun as a carrot to encourage myself to finish The Club Dumas.

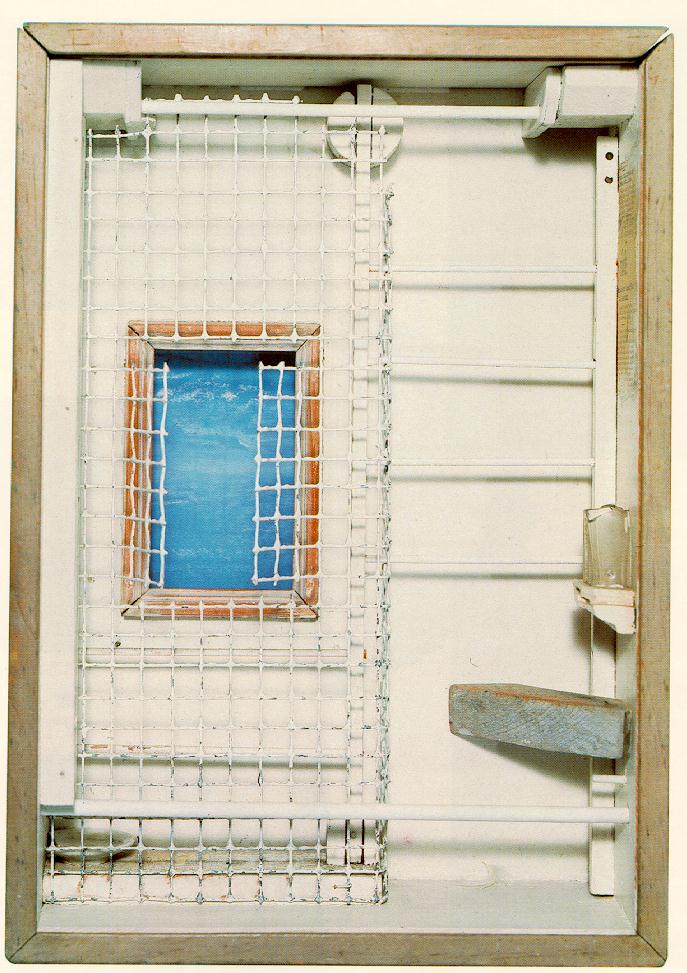

A Loaded Gun is not a straight biography of Emily Dickinson. If you are looking for a chronological narrative of Dickinson’s life, this biography will likely not satisfy you. However, if you are interested in looking at Emily Dickinson with fresh eyes, casting away the stories you heard about her reclusive nature and her white dress, then this book is definitely the book for you. A Loaded Gun is really more the story of Dickinson’s genius. She is compared to and contrasted with other artists that we have struggled to understand—memorably, Joseph Cornell, who made shadow box art. This is his piece based on the work of Emily Dickinson, entitled Toward the Blue Peninsula:

The piece is inspired by the following poem (Fr. 535, Dickinson’s exact language and punctuation):

It might be lonelier

Without the Loneliness—

I’m so accustomed to my Fate—

Perhaps the Other—Peace—

Would interrupt the Dark—

And crowd the little Room—

Too scant—by Cubits—to contain

The Sacrament—of Him—

I am not used to Hope—

It might intrude opon—

It’s sweet parade—blaspheme the place

Ordained to Suffering—

It might be easier

To fail—with Land in Sight—

Than gain—my Blue Peninsula—

To perish—of Delight—

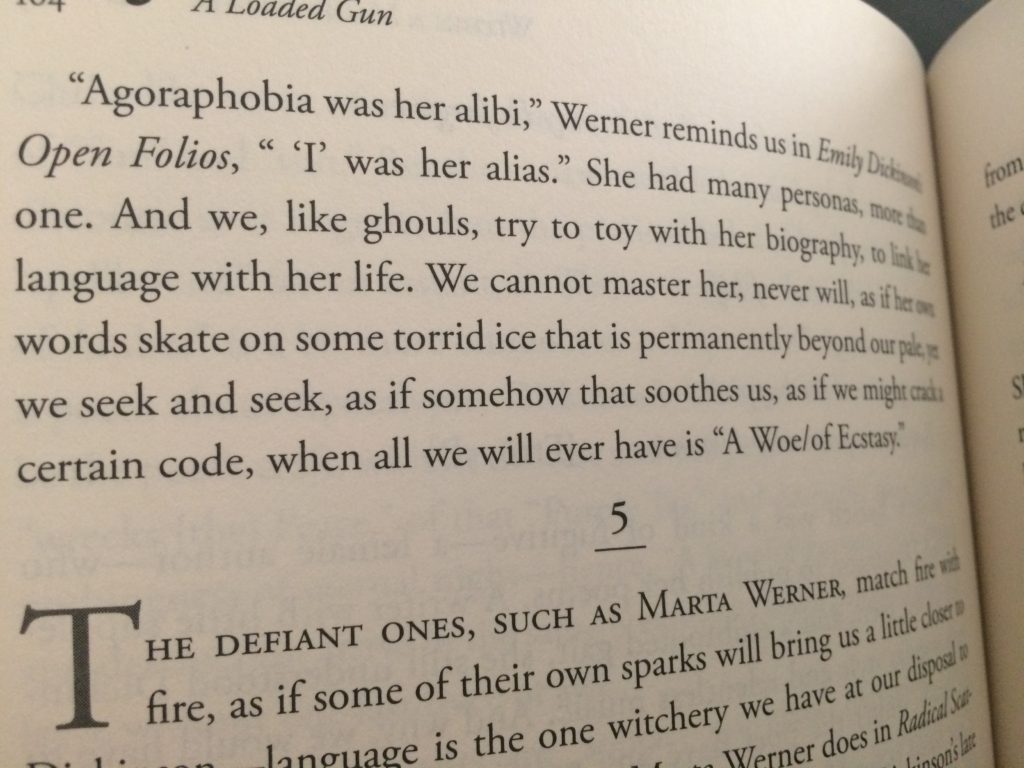

Charyn spends the bulk of one of his chapters discussing Cornell’s art and connecting it to Dickinson’s. Ultimately, however, Charyn finds Dickinson elusive. As he says in his introduction, “I know less and less the more I learned about her” (8). I snapped a photo of the following page, with discussion of one of the most “well-known” facets of Dickinson’s life:

One thing that is clear to me after reading this book is that we may never really know Emily Dickinson at all. Who was this genius who played with language in a way no other American poet has matched?

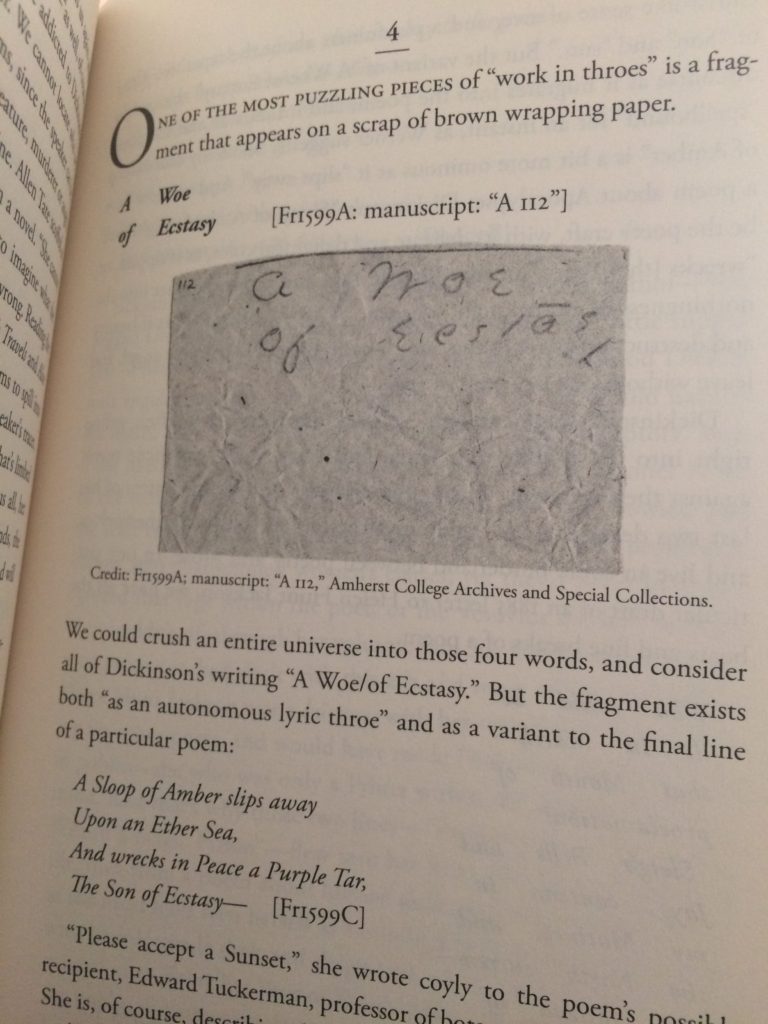

If you haven’t seen the way Emily Dickinson thought about variant word choices, you should definitely take a look at some of her poems. The Dickinson museum has one such poem posted as a display, and visitors can try out Dickinson’s different word choice ideas by moving levers (they don’t allow photography, so I can’t share a picture of it, but it’s really interesting). Dickinson marked her variant word choices with a + and wrote the variations in the margins and on the bottom of the page. Because Dickinson didn’t publish her work, it’s hard to say which variations she would ultimately have preferred, and in some ways, I absolutely love the freedom I have as a reader, if I see Dickinson’s original work, to construct my own favorite version of her poems. Ultimately, her editors have had to make the decisions that Dickinson did not make, and I’m not always sure I agree with their choices.

As he did in his lecture, Charyn discussed the possibly new daguerreotype discovered by “Sam Carlo” in a Great Barrington, MA junk shop. I had a chance to talk a little bit with Sam Carlo at Charyn’s talk, and he also let me take a picture of his replica of the daguerreotype. Charyn, like Sam Carlo, believes the other woman in the daguerreotype was Kate Scott, and Charyn advances the theory that Dickinson was in love with Scott, and also that she was in love with her sister-in-law Susan Dickinson (this theory is not new—Charyn said at his lecture that if you read Dickinson’s letters to her sister-in-law, there really isn’t another way to interpret them except as love letters; I plan to read them and see what I think). Was Emily Dickinson a lesbian? Bisexual? Charyn argues that partly, our picture of Emily Dickinson has been the virginal spinster in white who never left the house, and the image of her in the known daguerreotype supports this vision of Dickinson. She remains forever fifteen in our imaginations rather than the grown woman who wrote fierce poetry.

I enjoyed Charyn’s book very much. One aspect I particularly liked is that he didn’t remove himself from the subject matter. He is a part of the story he is telling as well. He describes visiting Vincent van Gogh’s room in Auvers-sur-Oise outside Paris.

And for the price of a few euros, collected by a ticket taker at a little kiosk in the rear yard, I climbed upstairs and visited van Gogh’s room. It was barren, with a tiny skylight and a cane-back chair; the walls were full of crust, the floor was made of barren boards, and I couldn’t stop crying. I imagined him alone in that room, his mind whirling with colors, his psychic space as primitive and forlorn as a lunatic’s world… he was always alone. (211)

Charyn doesn’t explicitly connect Dickinson’s room to van Gogh’s. Perhaps he wants the reader to make that connection if he/she so chooses. I don’t know if I will ever forget ascending the stairs the first time I visited Emily Dickinson’s house and seeing the sunlight illuminating the replica of Emily’s white dress on a dressmaker’s dummy. The docent told us a story about Dickinson pretending to lock her door and telling her niece, “Matty, here’s freedom.” What freedom did Dickinson find in that small room?

Even her poetry on the subject is elusive:

Sweet hours have perished here,

This is a timid room—

Within its precincts hopes have played

Now fallow in the tomb. (Fr. 1785)

R. W. Franklin’s edition of her poems differs from Thomas H. Johnson’s edition:

Sweet hours have perished here;

This is a mighty room;

Within its precincts hopes have played,—

Now shadows in the tomb. (1767)

Which was it? If I had my way, it would go like this:

Sweet hours have perished here;

This is a mighty room;

Within its precincts hopes have played,—

Now fallow in the tomb.

I suppose part of the beauty of Emily Dickinson in the 21st century is that now we know more about what she actually wrote, including all her variant word choices. All the layers of changes made by editors over the years have been stripped bare. We can look at Dickinson’s original manuscripts and examine her poems in Franklin’s Variorum Edition. As a result, the poet we thought we knew and understood is more elusive than before. Still, she remains as intriguing a subject of study as she ever was—perhaps even more than she was when we assumed she was a waifish, homebound spinster in white.

Rating: