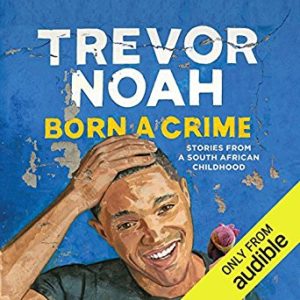

Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah

Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah Narrator: Trevor Noah

on November 15, 2016

Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

Format: Audio

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

The compelling, inspiring, (often comic) coming-of-age story of Trevor Noah, set during the twilight of apartheid and the tumultuous days of freedom that followed.

One of the comedy world's brightest new voices, Trevor Noah is a light-footed but sharp-minded observer of the absurdities of politics, race, and identity, sharing jokes and insights drawn from the wealth of experience acquired in his relatively young life. As host of the US hit show The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, he provides viewers around the globe with their nightly dose of biting satire, but here Noah turns his focus inward, giving readers a deeply personal, heartfelt and humorous look at the world that shaped him.

Noah was born a crime, son of a white Swiss father and a black Xhosa mother, at a time when such a union was punishable by five years in prison. Living proof of his parents' indiscretion, Trevor was kept mostly indoors for the first years of his life, bound by the extreme and often absurd measures his mother took to hide him from a government that could, at any moment, take him away.

A collection of eighteen personal stories, Born a Crime tells the story of a mischievous young boy growing into a restless young man as he struggles to find his place in a world where he was never supposed to exist. Born a Crime is equally the story of that young man's fearless, rebellious and fervently religious mother—a woman determined to save her son from the cycle of poverty, violence, and abuse that ultimately threatens her own life.

Whether subsisting on caterpillars for dinner during hard times, being thrown from a moving car during an attempted kidnapping, or just trying to survive the life-and-death pitfalls of dating in high school, Noah illuminates his curious world with an incisive wit and an unflinching honesty. His stories weave together to form a personal portrait of an unlikely childhood in a dangerous time, as moving and unforgettable as the very best memoirs and as funny as Noah's own hilarious stand-up. Born a Crime is a must read.

A colleague recommended that I read this book, though it had been sort of on the periphery of my radar for some time, as I enjoy Trevor Noah on The Daily Show and had heard good things about his memoir. My colleague said that listening to the audiobook was especially a treat, and my advice is that if you do read this book, do yourself a favor and let Trevor Noah read it to you. He is an incredible narrator, and hearing the memoir in his own words definitely added to my enjoyment of the book.

Trevor Noah had one heck of a childhood. He comes across as resourceful, clever, and funny, but it’s clear that he learned all of these attributes from his mother, Patricia, who emerges in many ways as the real hero of Trevor Noah’s memoir. I dare you to read this book and not cry at the very end. She is an incredibly strong woman, and Noah’s love for her shines through the entire book.

Moments of the book will have you laughing out loud, while others will make you cry. Born a Crime is a fantastic memoir, gripping and engaging from start to finish. You will definitely walk away from it with admiration for Trevor Noah’s strength… and his mother’s.

I’m counting this book for January’s motif in the Monthly Motif Challenge: New to You Author. I think this is Trevor Noah’s only book; I haven’t read anything he’s written before.

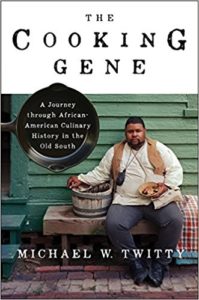

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by