I just returned from the annual National Council of Teachers of English conference. Alison Bechdel was a keynote speaker Friday morning, and she spoke about her two graphic memoirs, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama, as well as her other work in comics. Her parents had both been English teachers, and she had much to share with us about encouraging writers and the ways in which her own parents shaped her as a reader and a writer.

I just returned from the annual National Council of Teachers of English conference. Alison Bechdel was a keynote speaker Friday morning, and she spoke about her two graphic memoirs, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama, as well as her other work in comics. Her parents had both been English teachers, and she had much to share with us about encouraging writers and the ways in which her own parents shaped her as a reader and a writer.

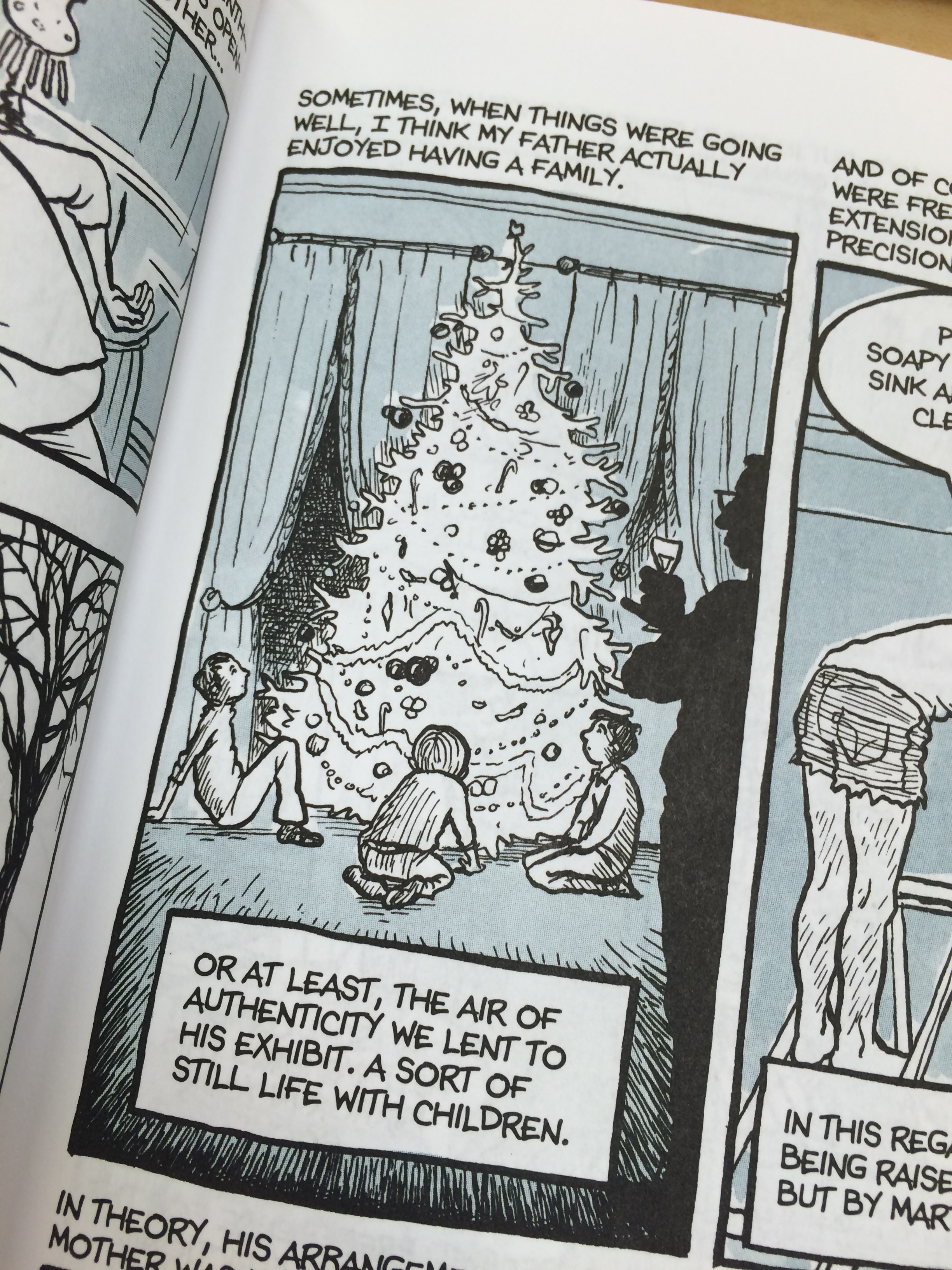

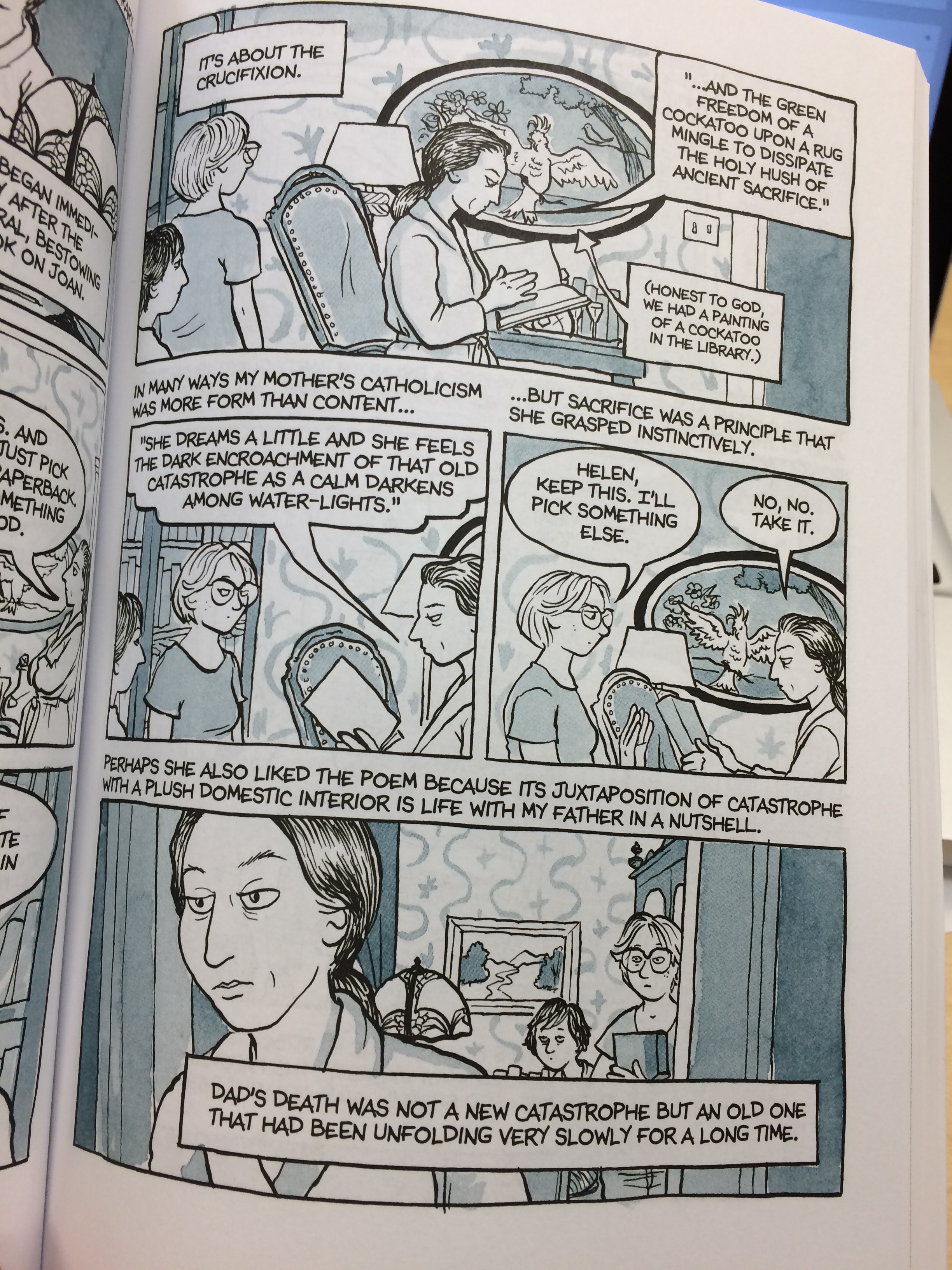

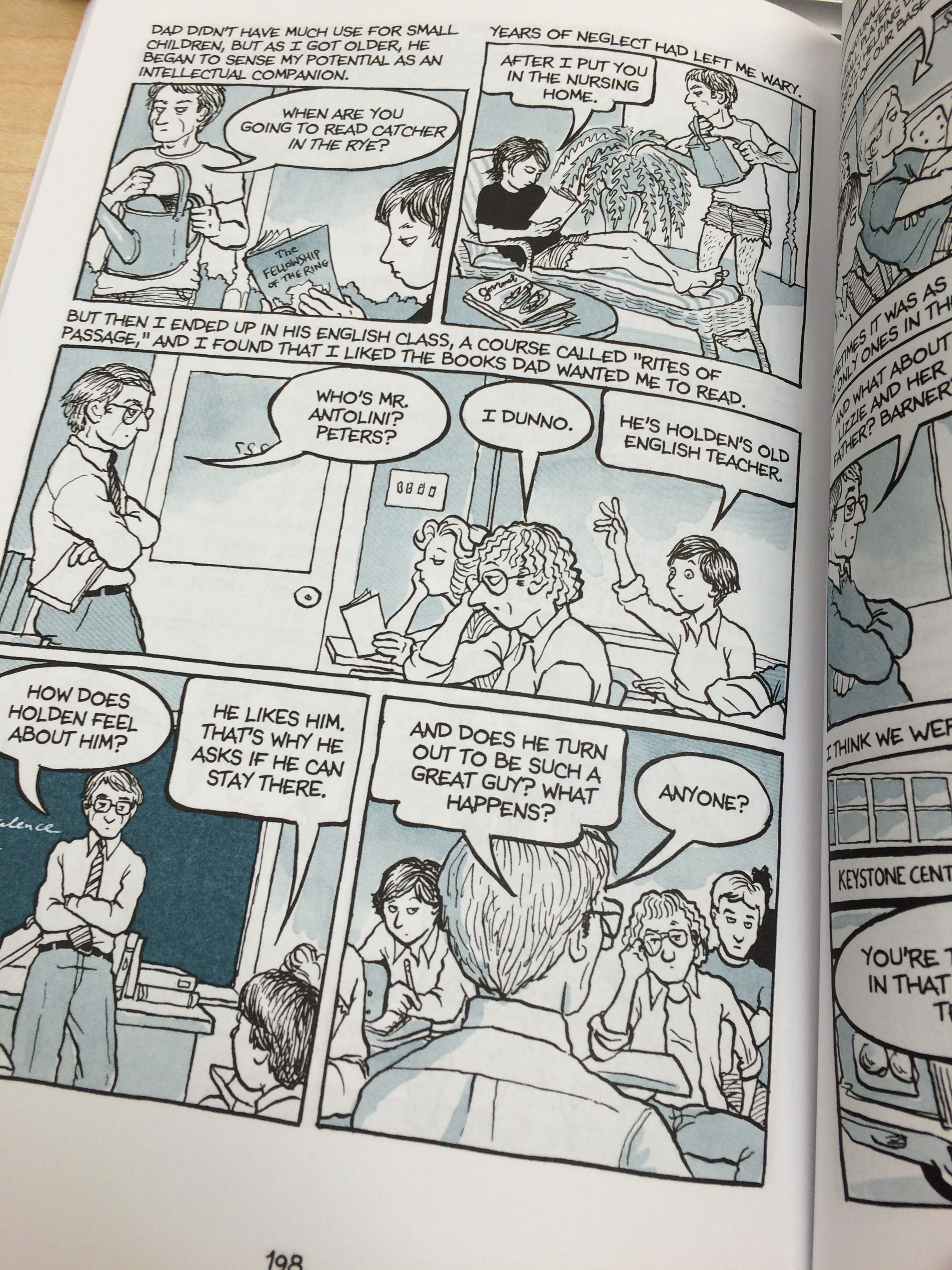

Fun Home centers on Bechdel’s relationship with her father, who likely committed suicide in 1980, right after Bechdel came out to her parents. Her father was a somewhat distant and arguably abusive man who was plagued by his own struggles with his sexual identity. Bechdel chronicles the family’s difficulties with her father, whose passion was restoration. His preoccupation with appearances profoundly affected Bechdel. She grew up in a very cold home.

But Bechdel’s father influenced her as a reader and writer.

Fun Home is packed with literary allusions, from her own identification of Bechdel’s father and herself as Daedalus and Icarus to her connection of her father to F. Scott Fitzgerald to finding herself in the writing of Collette and other LGBT writers. There is a good interview with Bechdel on NPR you might want to check out if you want to learn more about her and also about the Broadway musical adapted from this book.

Fun Home is packed with literary allusions, from her own identification of Bechdel’s father and herself as Daedalus and Icarus to her connection of her father to F. Scott Fitzgerald to finding herself in the writing of Collette and other LGBT writers. There is a good interview with Bechdel on NPR you might want to check out if you want to learn more about her and also about the Broadway musical adapted from this book.

I truly enjoyed this book. I read it while waiting in the airport to return home from the conference and finished it on the plane. It’s a quick read, but an absorbing and very deep read. It’s a well-written memoir on top of being poignant. There are moments of levity, even in panels in which Bechdel is dealing with her father’s death.

If you are not familiar with Bechdel’s work, you probably have at least heard of the “Bechdel Test,” which is a criterion for determining whether a movie has some consideration of women as fully realized characters to the following extent:

- It has to have at least two women characters

- Who talk to each other

- About something other than a man

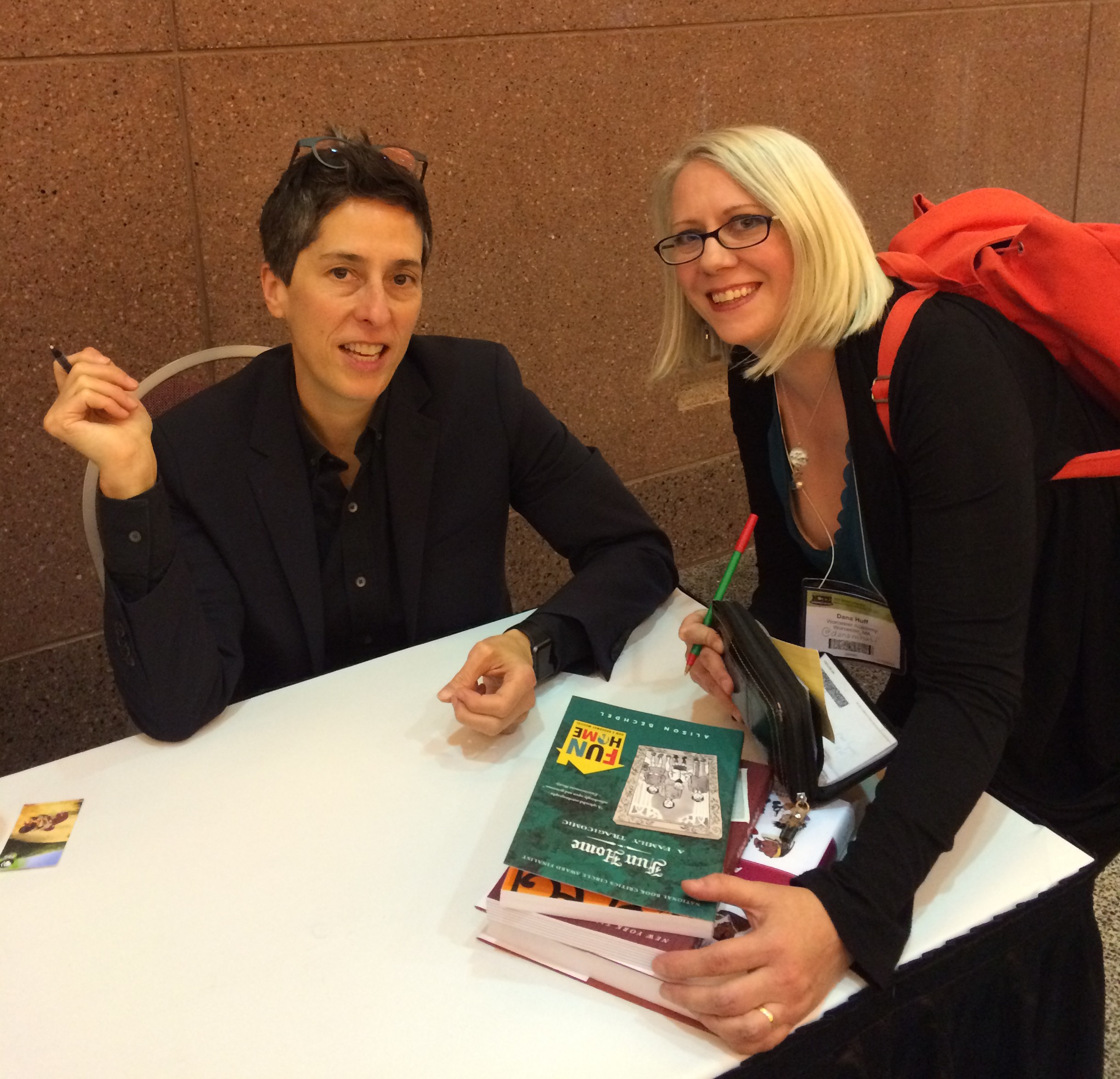

I was fortunate to be able to meet Alison Bechdel at the conference, and she signed my copy of this book.

It was wonderful to meet her and hear her speak about her reading and writing life.

It was wonderful to meet her and hear her speak about her reading and writing life.