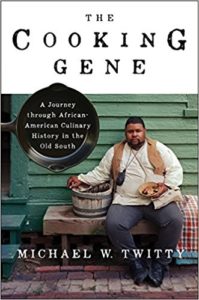

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by Michael W. Twitty

The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South by Michael W. Twitty Published by Amistad on August 1st 2017

Genres: Nonfiction

Pages: 464

Format: E-Book

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

A renowned culinary historian offers a fresh perspective on our most divisive cultural issue, race, in this illuminating memoir of Southern cuisine and food culture that traces his ancestry—both black and white—through food, from Africa to America and slavery to freedom.

Southern food is integral to the American culinary tradition, yet the question of who "owns" it is one of the most provocative touch points in our ongoing struggles over race. In this unique memoir, culinary historian Michael W. Twitty takes readers to the white-hot center of this fight, tracing the roots of his own family and the charged politics surrounding the origins of soul food, barbecue, and all Southern cuisine.

From the tobacco and rice farms of colonial times to plantation kitchens and backbreaking cotton fields, Twitty tells his family story through the foods that enabled his ancestors’ survival across three centuries. He sifts through stories, recipes, genetic tests, and historical documents, and travels from Civil War battlefields in Virginia to synagogues in Alabama to Black-owned organic farms in Georgia.

As he takes us through his ancestral culinary history, Twitty suggests that healing may come from embracing the discomfort of the Southern past. Along the way, he reveals a truth that is more than skin deep—the power that food has to bring the kin of the enslaved and their former slaveholders to the table, where they can discover the real America together.

I first heard about The Cooking Gene on the Gastropod podcast some months back. I have embedded the episode below. Gastropod is an interesting podcast that focuses on food and science (and sometimes history).

I preordered Twitty’s book for my Kindle app, but I didn’t start reading it in earnest until December. It’s an unusual combination of genealogy research, personal memoir, and food history. Twitty has been able to travel to Africa since he finished the book—something I know from following him on Twitter. The pages of this book make clear how much Twitty honors his ancestors and the food and folkways they developed as slaves in the American South. Twitty re-enacts historical cooking at Colonial Williamsburg and came to the national forefront when he offered Paula Deen a chance at redemption through cooking a meal together with him and his subsequent Southern Discomfort Tour. What a shame Ms. Deen ignored his invitation. She would have learned something from him, judging by this book.

I recognized many of the folkways and foodways in my own family in the pages of this book, which is no surprise given my family on my mother’s side is Southern and migrated from Virginia through the South to Texas by the 2oth century. One image particularly resonated with me:

I grew up with a grandmother who would make cornbread several times a week and take any that was left over the next day, crumble it into a glass of buttermilk, and eat it out with a spoon. The glass streaked with lines of buttermilk and crumbs grossed me out. But when I asked my grandmother why she did it that way, she replied, without explanation, “At least I didn’t have to eat it from a trough” (199).

As Twitty later explains, enslaved children ate a cornmeal mush out of a trough at midday. The image of Twitty’s grandmother at the kitchen table eating cornbread and buttermilk reminded me of my own image of my grandmother doing the same thing. My reaction when I was a child was similar to Twitty’s. I don’t think I asked her why she ate it that way, but I’m confident it had been passed down in her family, probably originating from slaves her family owned.

I would recommend this book to anyone interested in learning more about American history, particularly Southern history and African-American history, as well as anyone interested in the history of food in America. Twitty says late in the book that “Culinary justice is the idea that people should be recognized for the gastronomic contributions and have a right to their inherent value, including the opportunity to derive empowerment from them” (409).

Finishing this book was a great way to start the year and to kick off my participation in the Foodies Read Challenge and the Monthly Motif Challenge, though truthfully, Michael Twitty’s family history stories are firmly bonded with my own in that my family was on the other side of the institution of slavery. The stories of white and black Southerners are inextricably linked. He even mentioned a friend named Tambra Raye Stevenson, a nutritionist from Washington DC, whose “‘furthest back person’ was a woman in the white family named ‘Mammy,” Henrietta Burkhalter, born a slave in Baltimore. Sold as a young girl to the Burkhalter family in Georgia, ‘Mammy’ trekked with the white family and her sons to Mississippi, then Texas, and finally rested her soul in McIntosh County, Oklahoma” (277). The Burkhalters are my cousins. My great-great-grandfather’s sister married into the family, and I have been to several family reunions with the Burkhalter bunch in Georgia, and yes, some of them went west to Texas, as did their Cunningham kin. What a small world. The goal of this month’s “motif” is to diversify my reading through reading an author of a “race, religion, or sexual orientation” than mine. Michael Twitty is all three as a black, Jewish, gay man, but he feels like family to me. And given his history, it’s entirely possible that he is a cousin. Be sure to check out his blog in addition to this book.