I always knew I would not meet the challenge goals I set for myself in 2019 because of graduate school. BUT. I will be done with my coursework in May, and even though I’ll still be conducting research and will begin my dissertation, I think I might just have a little bit more time to read what I want to read in 2020. I did plenty of reading. I did A LOT of reading. It was graduate school reading, though.

I enjoy participating in reading challenges because they help me define reading goals, so I have selected the following reading challenges. However, I need to be a bit more realistic this year and pare it down. I am just going to participate in four challenges.

I like to do the Historical Fiction Reading Challenge each year because historical fiction is my favorite genre. I will shoot for the Victorian Reader level of five books. If I have a good reading year, I may increase it, but we will see what happens. I do not know yet what I will read, but I know one of the books will be the third book in Hilary Mantel’s trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, which is due out in March.

I like to do the Historical Fiction Reading Challenge each year because historical fiction is my favorite genre. I will shoot for the Victorian Reader level of five books. If I have a good reading year, I may increase it, but we will see what happens. I do not know yet what I will read, but I know one of the books will be the third book in Hilary Mantel’s trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, which is due out in March.

I am signing up for a new-to-me challenge called the Social Justice Nonfiction Challenge 2020. I had planned some reading along these lines already, and I am hoping to identify books I might not otherwise have heard about through this challenge.

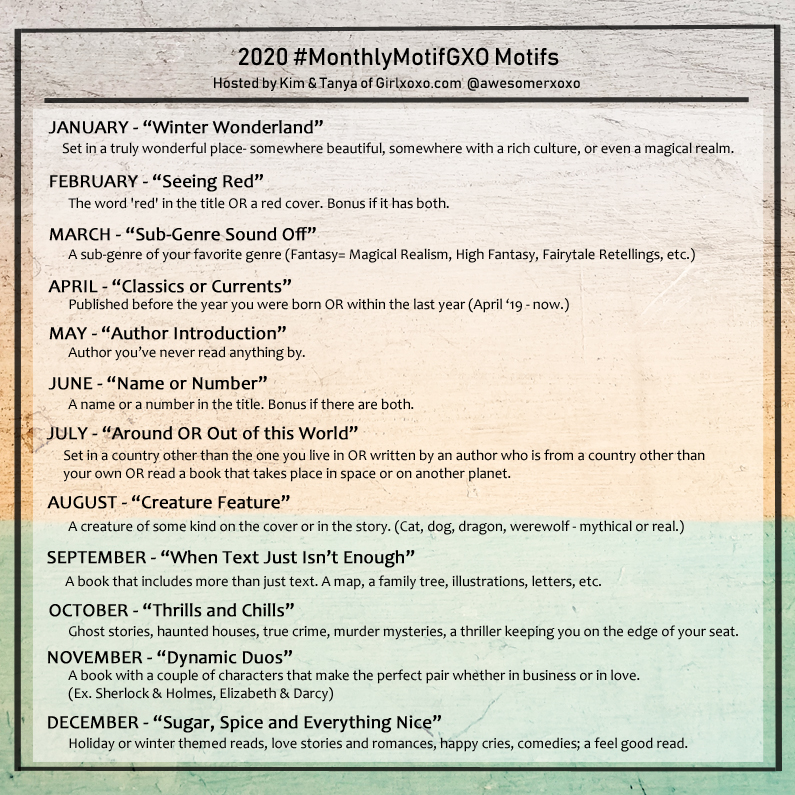

I have enjoyed participating in the Monthly Motif Challenge the last couple of years, even though I haven’t finished it. It gives my reading a fun focus. I am not sure what books I will read. I kind of like playing it by ear. They have some fun motifs planned for this year.

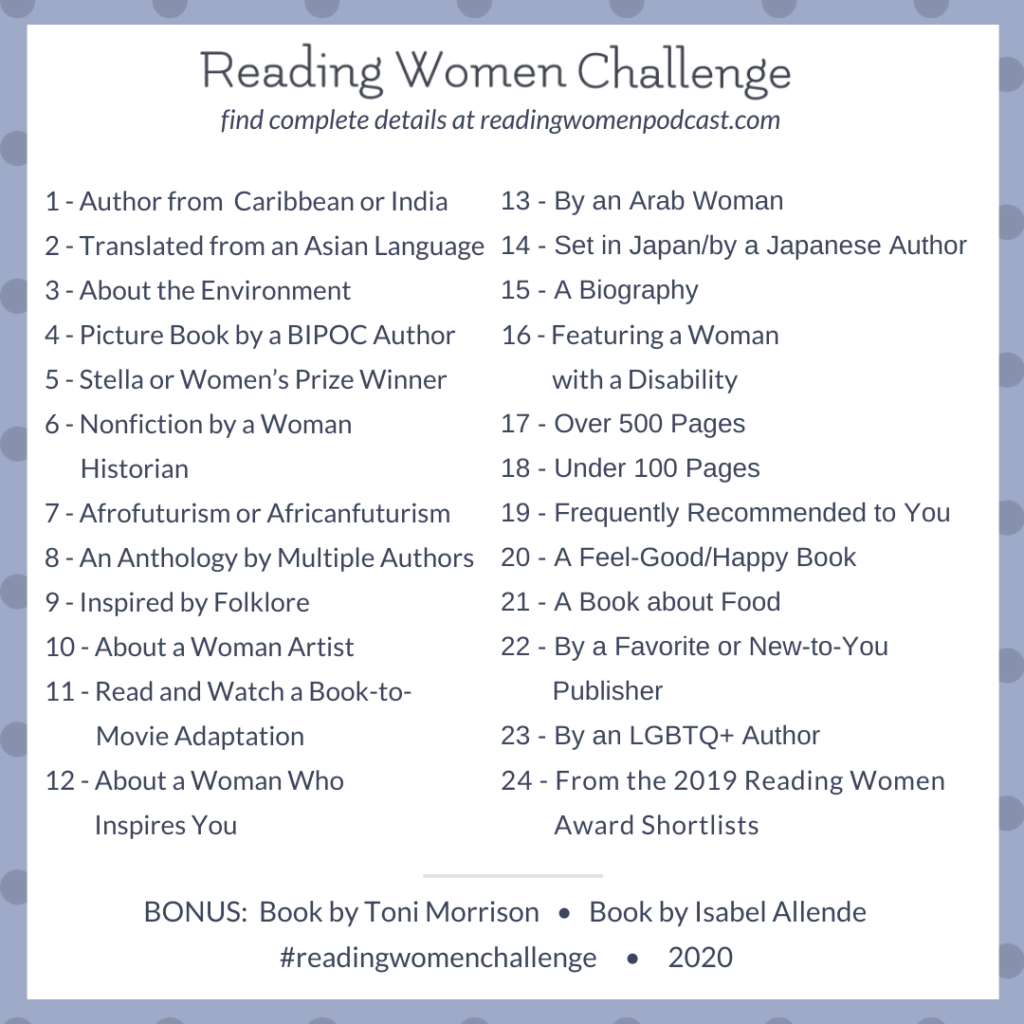

Last year was my first year participating in the Reading Women Challenge. Again, I didn’t come close to finishing, but I really like the look of their suggested list.

1919 by

1919 by

Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by

Born A Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by  There There by

There There by

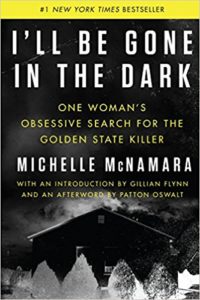

I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by

I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by

I Am Not Your Negro by

I Am Not Your Negro by

The Movement of Stars by

The Movement of Stars by  The Miniaturist by

The Miniaturist by

Stonewall by

Stonewall by