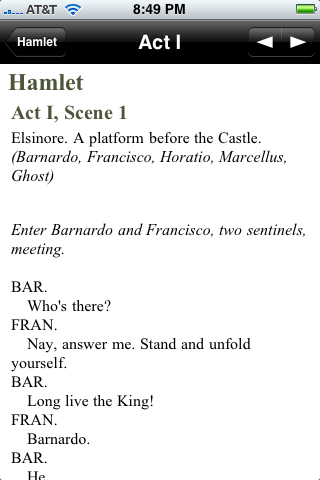

As an English teacher, I have become familiar with a few of Shakespeare’s plays. I’ve taught Romeo and Juliet so many times that I have huge chunks of it memorized. I’ve taught Macbeth several times, too, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Taming of the Shrew, Othello, King Lear, Hamlet, Much Ado About Nothing, and Julius Caesar.

As an English teacher, I have become familiar with a few of Shakespeare’s plays. I’ve taught Romeo and Juliet so many times that I have huge chunks of it memorized. I’ve taught Macbeth several times, too, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Taming of the Shrew, Othello, King Lear, Hamlet, Much Ado About Nothing, and Julius Caesar.

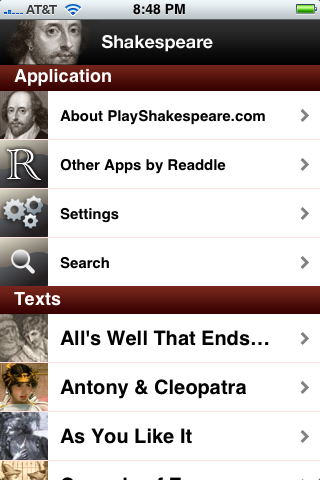

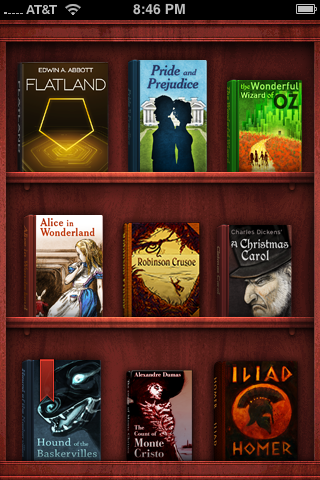

However, there are several plays I’ve never read or read back in my Shakespeare course in undergrad so long ago that I don’t remember them well. To that end, I decided to participate in the Shakespeare Challenge at the Desdemona level (6 plays, 2 of which can be replaced by performance). I’m not sure exactly which six I’ll read, but I definitely want to read As You Like It and The Tempest. Aside from these two “definitelys,” I have the following “maybes” in mind:

- The Merchant of Venice

- Richard II

- Cymbeline

- Coriolanus

- Antony and Cleopatra

- Titus Andronicus

- Twelfth Night

- A Winter’s Tale

Stay tuned for an announcement about a reading challenge I’ll be hosting on this blog for next year. Hint: it is somewhat related to this reading challenge.

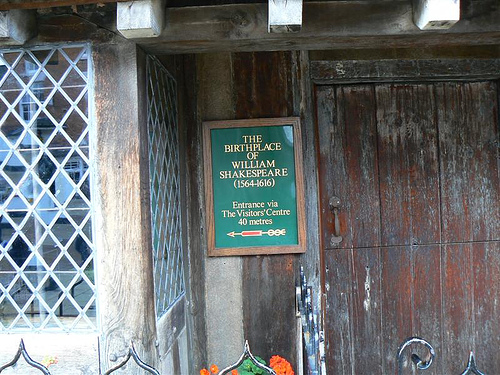

Image ©The Folger Shakespeare Library (I think).