My grandfather passed away in April, two weeks before his 95th birthday. He was my last living grandparent, and we were close. When I was about nine, he got me started on a stamp collection. He took me to the hobby shop in the shopping center about a quarter of a mile from his house, and he selected a starter stamp album for me. He bought a package of hinges to fasten stamps into the album. He probably also bought me a grab bag of loose used stamps, some of them still stuck to a corner of an envelope. He showed me how to use the album, which had tiny pictures of the stamps. These albums are helpful for beginners because once you find the picture of my stamp, you just affix the stamp to the image using a hinge. Papa showed me how I could put a used stamp that was still stuck to the envelope in a small bowl of warm water, and it would separate from the paper without tearing. Then I could dry the stamp on a paper towel and affix it to my album with a hinge.

He donated stamps from his own collection to help me get started. He collected stamps from all over the world. I remember being confused about the country of origin of one of the stamps, and he helped figure out where to put it, explaining that there were “two Chinas.” I didn’t understand what he meant, but I realized later it must have been a generational difference—I had only ever known the country he called the “second China” as Taiwan. I learned a lot about history and geography from collecting stamps.

My own collection was never large. I took up the hobby again in my 20s, but unfortunately, I couldn’t really afford it at the time, so I set aside the collecting for a while. I inherited my grandfather’s collection, which might not be considered large in philatelic circles, but it’s much larger than mine ever was. He appears to have stopped collecting stamps himself around the time I was born, or at least his albums don’t appear to date past the early 1970s. He has albums dedicated to the countries of France, Germany, Japan, Great Britain (the United Kingdom), and the U.S.A. He also has many stock albums and a few handmade albums with carefully drawn templates and typed on what I recognize as his old Royal typewriter.

The stamps in his U.S. album are mounted, while the other stamps all appear to be affixed to their albums with hinges. I think a long time ago, hinges were considered relatively harmless, but these days, many collectors prefer mounts. Mounts are affixed to the album, but they do no damage to the stamps themselves, unlike hinges, which sometimes disturb the gum or the paper on the back of the stamp.

Stamp albums are really expensive, and I wouldn’t be able to find some of the albums Papa used anymore—maybe on eBay, but certainly not easily. I plan to preserve his collection and perhaps add to it, but I wanted to replace all his hinges with mounts. This is the title page of his British stamp album.

Its copyright date is 1959. I don’t have much to compare it to, but I suspect it might be a more comprehensive British stamp album than one made in the U.S. Stanley Gibbons is a stamp merchant in the U.K. The edges of the page are lighter. I am not sure what caused the discoloration, but I suspect maybe the paper on the part of the cover touching the title page is not acid-free. The pages in the rest of the album seem fine, but all the more reason to mount the stamps. I wouldn’t want them to become discolored, too.

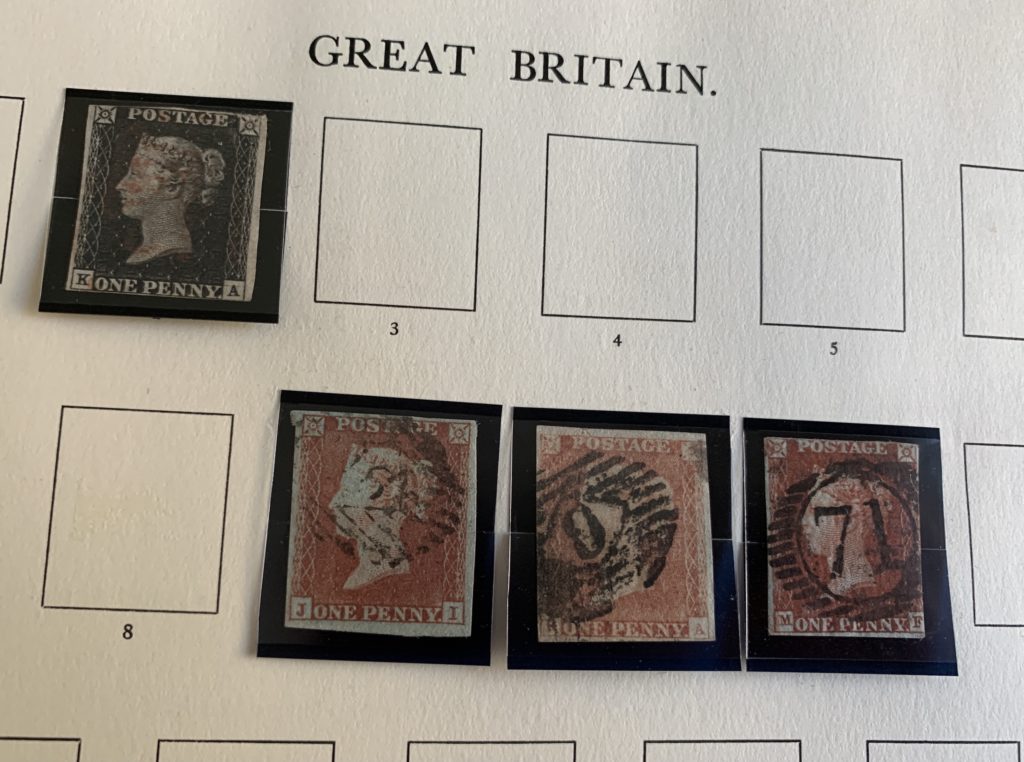

I discovered the pre-cut mounts I ordered were a bit too big, so I ordered some mount strips and a little craft guillotine so I could cut the mounts to the correct size. My last supply order arrived today, so I started working on Papa’s Great Britain album. This is the first page.

The stamp in the upper left is known as a “Penny Black.” Penny Blacks were the first postage stamps. They’re not exceedingly rare, but I think just about every collector wants one. If you are collecting stamps, you want to have the first postage stamp in your collection. The Penny Black was issued for less than a year—May 1840 to February 1841. The reddish cancelation you can see on the stamp was apparently easy to remove, and people reused the stamps, so the British postal service decided to change the stamp’s color to red and use black cancelation, which would be harder to remove. This stamp was called a “Penny Red.” I don’t know if you can tell, but the first stamp with the letters J and I in the corner is actually on blue paper. The three stamps in the second row date from about 1841.

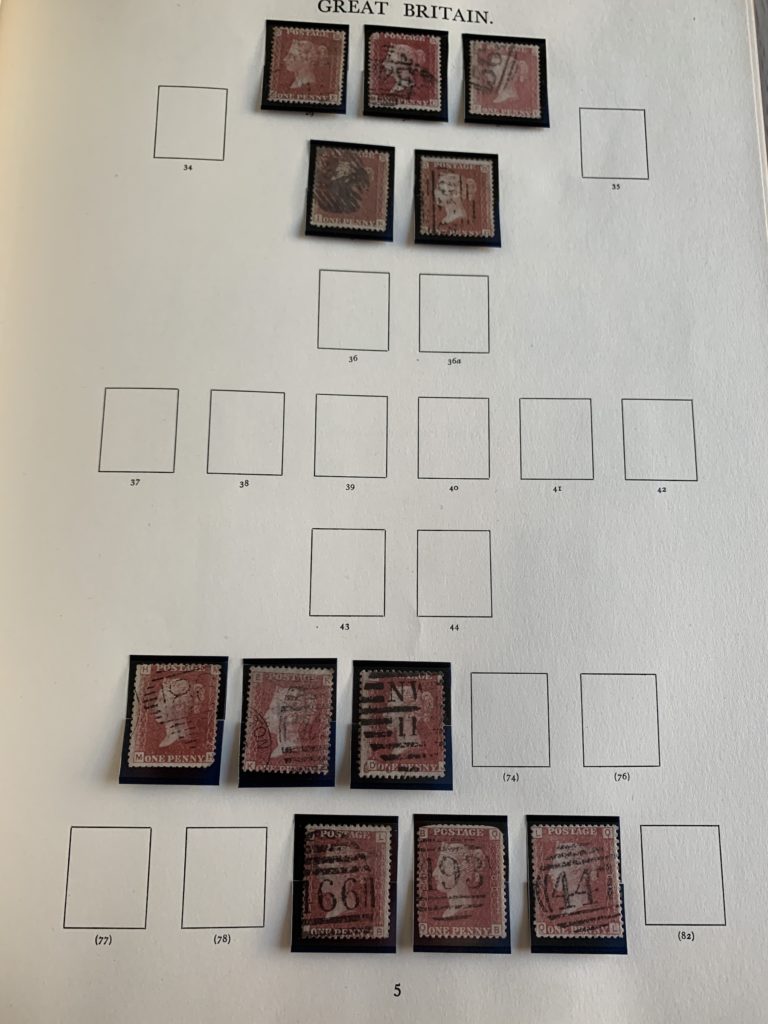

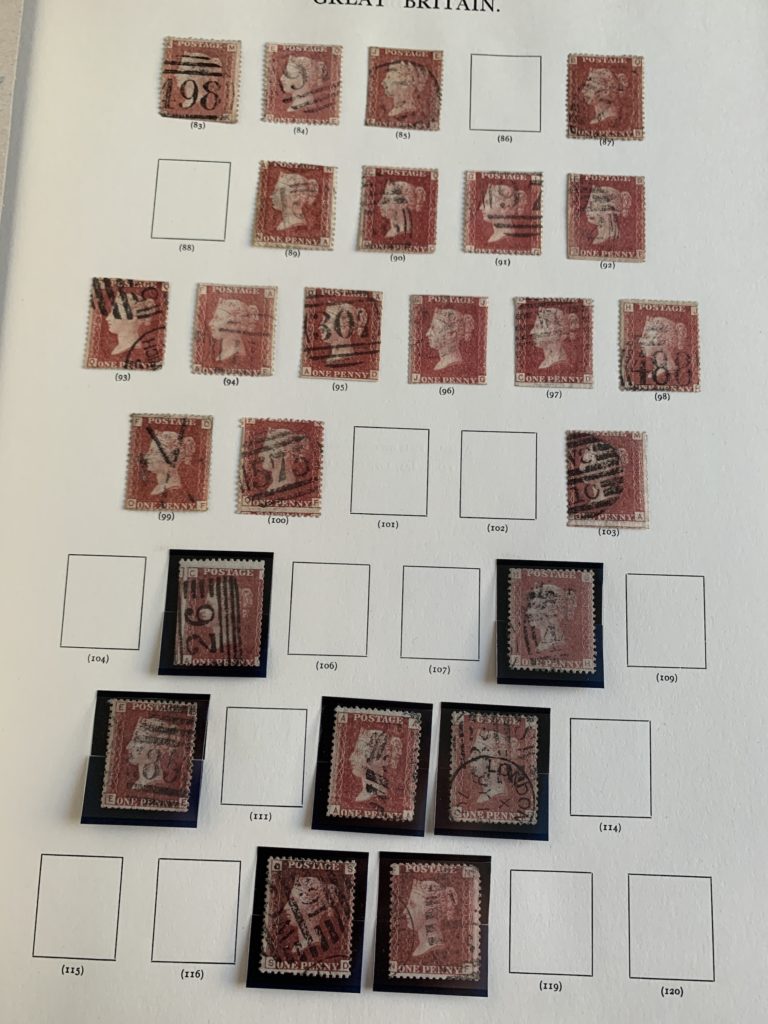

This next page includes stamps with a similar design, but they were issued later. The stamps at the top date from 1854-1857. The ones on the bottom date from 1858-1879. You probably can’t see this because I can only barely detect it with a magnifying glass, but the stamps on the bottom row have plate numbers in their frames on each side. The plate number is what it sounds like: the number given to the plate used to print the stamps. Plate numbers started appearing on Penny Reds in 1864.

Papa doesn’t have a complete collection of Penny Reds with each plate number, but it’s clear the album was designed for a serious collector who might want to have a copy of a Penny Red from each plate.

Here is another page of Penny Reds with plate numbers. I took a picture of this page in the middle of replacing the hinges with mounts. You can see the mounted stamps on the bottom and the hinged stamps on the top. While I admit I love the way the hinged stamps look in the album, the stamps will be better preserved in mounts. Papa placed the stamps into the album so carefully.

Partway through this project, I realized that someone had written the stamp’s Scott Number and plate number on the back of the stamps.

The Scott Number is the individual number given to each stamp by the Scott Catalogue, a comprehensive list of every stamp produced. Most collectors use Scott Numbers to refer to stamps. The Scott Catalogue also sets the basic value for a stamp, though the value is generally fluid and something that the buyer and seller agree on rather than anything fixed. The Scott Number for this stamp is 33, which was produced from 1864-1879. The plate number for this stamp is 103. The stamps vary in value depending on the plate number. This is not my grandfather’s handwriting. I am not sure who wrote the Scott and plate numbers on the backs of his stamps, but most of his Penny Reds have this information penciled on the back of the stamp. I suspect Papa may have bought or traded for another philatelist’s collection, and perhaps a previous owner penciled these numbers on the stamps. It was a fascinating find, though I suspect it would decrease the value of the stamps. The handwriting is extremely small. Even if I wanted to erase the numbers, I might damage the stamps in doing so.

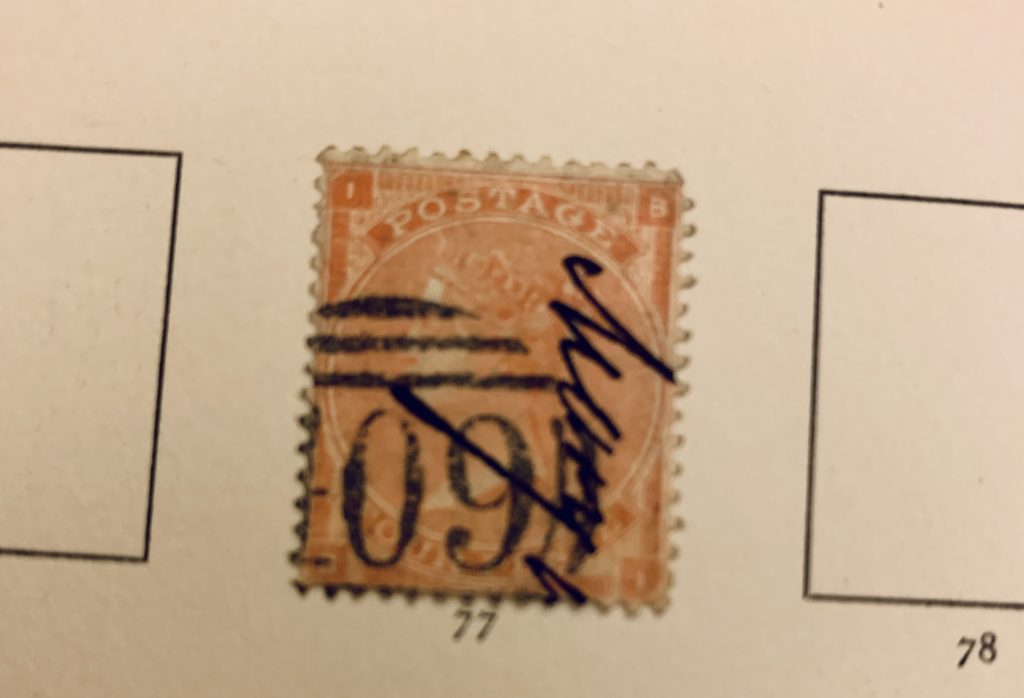

Further on into the collection, I found this stamp with what might be a partially handwritten cancelation. In any case, there is some black handwriting on the stamp.

I think Papa thought this stamp was a Scott 34, but I think it’s probably a Scott 43 based on the color and the way the letters in the corners of the frame look. I don’t know the corresponding Stanley Gibbons Windsor Number for the stamp. I guess I’ll need to get a copy of the Stanley Gibbons catalogue so I can compare. To be fair to Papa, the previous collector who penciled numbers on the backs of the stamps wrote the number “34” on the back, and the two designs are pretty similar.

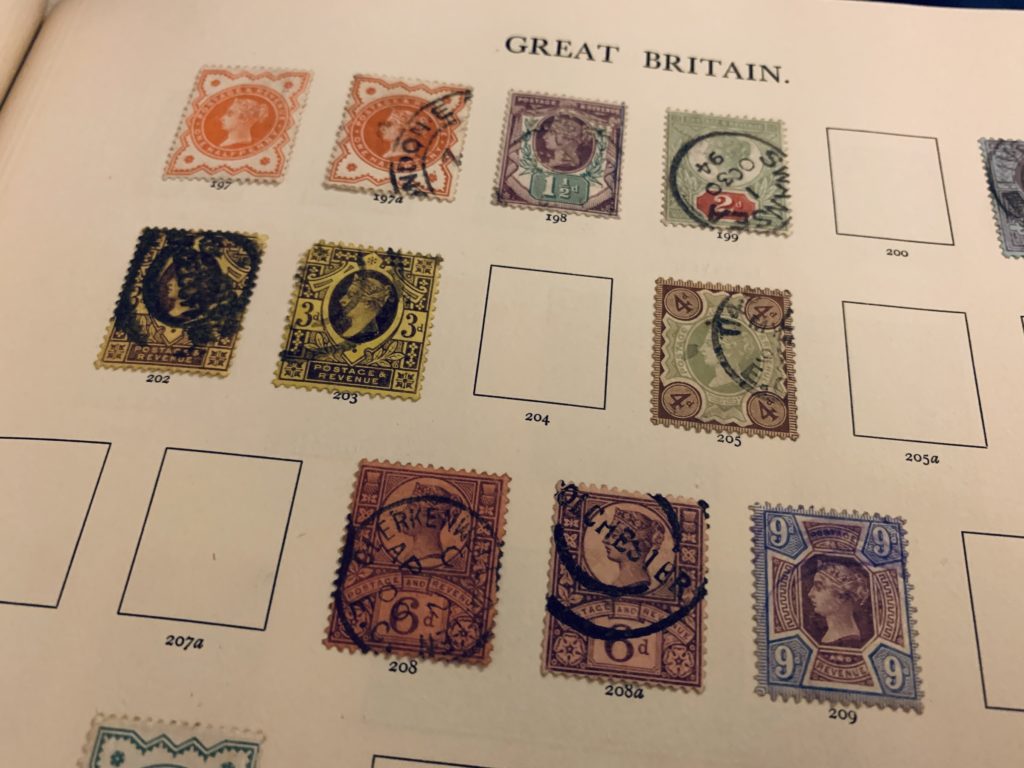

I found Papa’s first mint (not used) stamps dating from about 1887 (the stamp in the upper left).

While this stamp is beautiful and is in great condition, it’s not worth very much (less than $2.00). I also think Papa has the order of the stamps 197 and 197a reversed. The one labeled 197 should be vermilion and the 197a is orange vermilion. I think the one above the label 197 looks more orange.

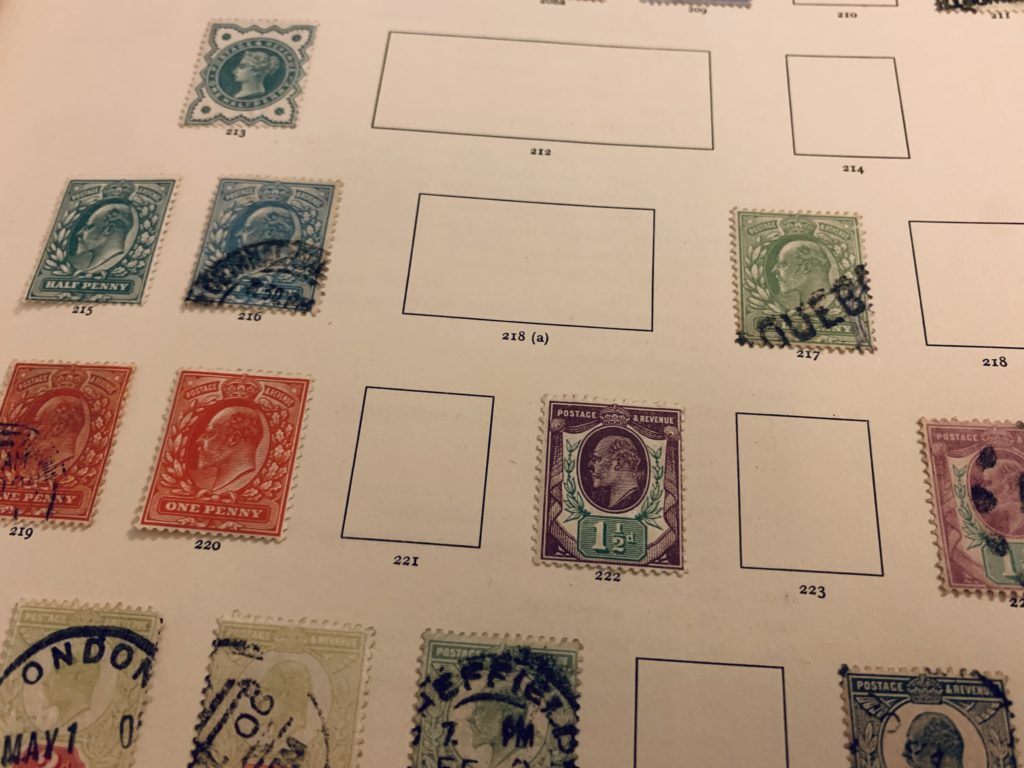

These stamps are on the bottom half of that same page. You can see a few more mint stamps: in the top row, a blue half-penny stamp featuring Queen Victoria, then in the next row a blue-green half-penny featuring Edward VII. In the third row are a scarlet one-penny and a 1½-pence in two colors. Stamps that are unused or mint and centered nicely with gum on the back (if any) intact, are more valuable than used stamps and/or stamps that are poorly centered or missing the gum.

It’s interesting how quickly all of this came back to me as I examined Papa’s stamps. It definitely made me want to build on his collection. It’s strange that I still think of it as his rather than mine. I am starting to think of them as my stamps, but not completely. It made me feel close to him again, to spend some time caring for his stamps and remember him sitting next to me at the coffee table in his house, showing me how to place my stamps into my album.

I don’t think I ever saw these stamps while Papa was alive. I know I would have wanted to spend hours flipping through the albums. I’m not sure why Papa stopped collecting stamps. As far as I can tell, based on what I see in the collection and based on what my Uncle Wayne told me, he collected stamps during the 1950s and 1960s. When my mother and Wayne were little, Papa worked in the post office, and I think he must have picked up the hobby at that time. Papa was something of a serial collector. He would spend a great deal of time on a collecting hobby and then move on to a new one. Wayne looked and looked for this stamp collection, and I think he had just about given up hope of finding it. When he finally found it, he called me and told me he’d bring it to me in person, as he and his girlfriend were going to stay in his girlfriend’s sister’s cottage on Cape Cod. We spent the day together. I was really moved that Wayne went to all that trouble to make sure I could have these stamps. I will treasure this collection. This is us at Cape Cod when we connected a couple of weeks back. (Don’t worry, we kept our masks on indoors, and I have had two negative COVID tests since—I wouldn’t risk his health, nor he mine).

Wayne looks so much like Papa. He told me all about how he used to go to stamp shows with Papa and collected a bit himself when he was young. He said that if not for those stamp shows, he might have started playing drums, which he’s done for 50 years. He said the stamp shows had live music, and he remembered being enthralled by the bands.

As soon as we arrived at the cottage, Wayne pulled out Papa’s stamps to show me. He had an old apple box full of albums. I don’t know that I can bear to toss out the box, even if I put the albums on a bookshelf at some point because Papa wrote “Automobile Quarterly” in his clear print on the top. At one time, he must have kept his issues of the magazine in that box. It was a publication devoted to collectible cars—another of Papa’s hobbies. Wayne will keep that particular collection. It isn’t that I don’t have anything in Papa’s handwriting. Once he sent me the longest letter I’ll probably ever receive, written on tablets, because I asked him to write down some of his stories.

I thought about Papa and my grandmother, who passed in 2016, this week as the 27th would have been their 70th wedding anniversary. I feel really blessed to have had them in my life and to have some of their things—a pair of Granna’s Gingher scissors and some spools of thread, a sewing machine foot, some thimbles, a packet of needles dating from the 1950s, an old package of stale Freedent gum, a tape measure, a business card… and Papa’s stamps.