Charles Dickens’s last novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood was incomplete at the time of Dickens’s death in 1870. In fact, he had finished half the book, which had been published in installments, a common practice with Dickens novels. When I heard Matthew Pearl’s lecture on this novel at the Margaret Mitchell House here in Atlanta last Monday, Pearl mentioned that reading books in installments is not something we as a reading public really understand. Sure, we have to wait for a television series like Lost to enfold in installments, but books are published whole and entire nowadays, and the thrill of reading the book as the writer is actually finishing it — that there is the chance no one yet knows how it will all turn out — is not available to us as readers as it was in Dickens’s time. To think — we will never know how his last novel turned out because no record of Dickens’s intentions with the novel has ever been found. We have the gift and frustration of creating our own ending. Perhaps it is for that reason, no matter how intrigued I was by the book based on reading Pearl’s novel, that I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to pick up The Mystery of Edwin Drood. I do think not knowing would drive me crazy.

Charles Dickens’s last novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood was incomplete at the time of Dickens’s death in 1870. In fact, he had finished half the book, which had been published in installments, a common practice with Dickens novels. When I heard Matthew Pearl’s lecture on this novel at the Margaret Mitchell House here in Atlanta last Monday, Pearl mentioned that reading books in installments is not something we as a reading public really understand. Sure, we have to wait for a television series like Lost to enfold in installments, but books are published whole and entire nowadays, and the thrill of reading the book as the writer is actually finishing it — that there is the chance no one yet knows how it will all turn out — is not available to us as readers as it was in Dickens’s time. To think — we will never know how his last novel turned out because no record of Dickens’s intentions with the novel has ever been found. We have the gift and frustration of creating our own ending. Perhaps it is for that reason, no matter how intrigued I was by the book based on reading Pearl’s novel, that I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to pick up The Mystery of Edwin Drood. I do think not knowing would drive me crazy.

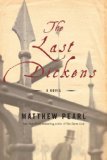

The hero of Pearl’s novel is James R. Osgood, one half of the publishing firm of Fields & Osgood, the Boston publishers of such luminaries as Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes, Emerson, and just about every other American writer of note at the time. This novel completes what Pearl thinks of as a literary set: the heroes of his first novel, The Dante Club, were the writers themselves; the hero of his second, The Poe Shadow, an admiring reader of Poe’s; The Last Dickens completes the reading trinity with a publisher. Pearl’s Osgood is a likeable fellow — a true champion of books, authors, and the reading public. He travels to England following Dickens’s death in the hopes that he can discover something, anything about Dickens’s intentions regarding the ending of Drood, only to find himself embroiled in Dickens family drama and the the seedy underbelly of the opium trade. Mysterious forces seem intent on discovering the ending of the novel for themselves either to pervert it toward their own ends or to destroy it.

Readers interested in learning more about Dickens, particularly the cult of celebrity surrounding his work, will enjoy this novel. The glimpses into the reality of life in Victorian England and Boston are interesting as well. Pearl’s characters seem so real that it may surprise you to read the historical note and discover several are invented for the book. I know I had to use my Ancestry.com membership to look up James R. Osgood in the census and find out if he was ever able to marry Rebecca Sand. One person asked Matthew Pearl about Dan Simmons’s new novel Drood, a thriller also inspired by Dickens’s last novel. The question revolved around the interest in The Mystery of Edwin Drood as inspiration, which Pearl explained as the fact that it remains unfinished and was the last Dickens novel. I wondered myself how both Pearl and Simmons felt upon arriving at such similar subject matter at the same time. It is my hope that the two novels will help each other rather than serve as competition. I know I am interested in reading Simmons’s novel now, and I’m not sure I would have been if Pearl hadn’t written The Last Dickens.

One thing I can say about Matthew Pearl is that he is one of the nicest and most personable writers you will ever meet. I first crossed his path when I recommended The Dante Club to my students in a blog post. He was appreciative and contacted me through my site, inviting me to hear his lecture upon the publication of The Poe Shadow. He held a trivia contest at the lecture, which I won. My prize was a manuscript page from The Dante Club (and it happened to be my favorite part of the book!). When I reached the end of the line and was able to have my books signed, I introduced myself, to which Matthew exclaimed, “Oh, you’re Mrs. Huff!” He signed my manuscript page, which I framed and hung on my classroom wall. Recently, he invited me to read an advance copy of The Last Dickens, and because I’m so slow, I’m just finishing it — I had hoped to have finished it before the novel itself was actually published so I could be one of the first reviewers. When I went to Matthew’s lecture at the Margaret Mitchell House, I was pleased that he remembered me and he asked about my students. Not all authors are so appreciative of their fans. I would read anything Matthew wrote, but truthfully, The Last Dickens is a good read that will appeal especially to book lovers.