Emily Dickinson declared, “Biography first convinces us of the fleeing of the Biographied.” Brenda Wineapple not only takes on the monumental task in White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson & Thomas Wentworth Higginson of writing a biography of the enigmatic Belle of Amherst, but also of her friend, now (unfortunately) mostly unknown except for his connection to Dickinson, Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

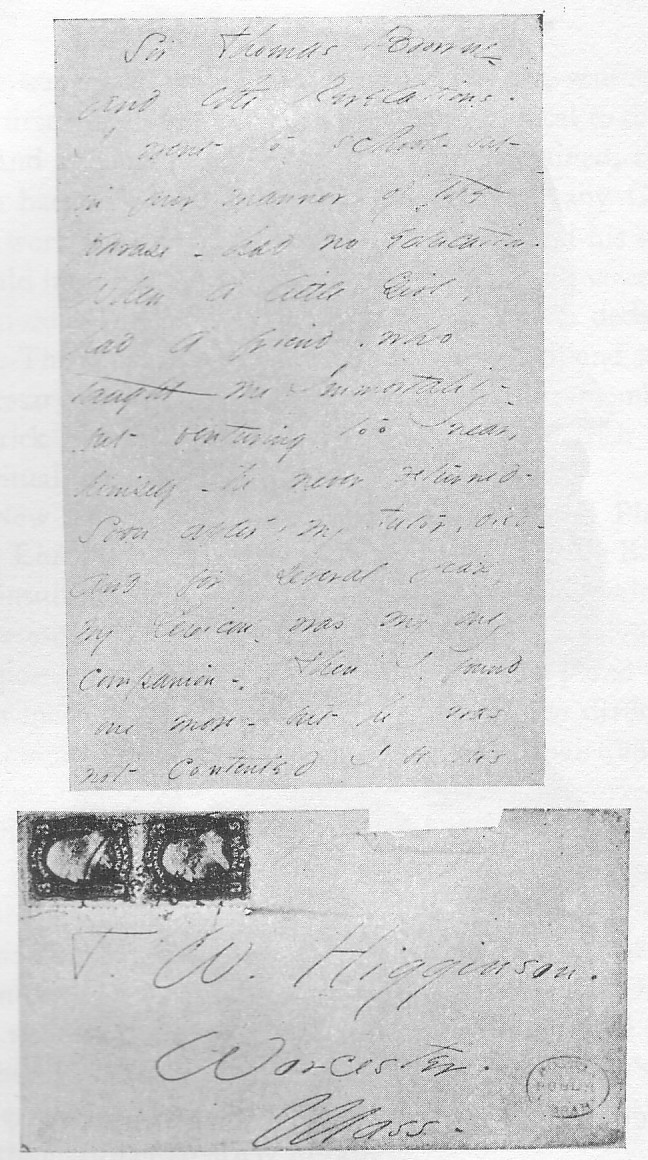

Dickinson sent her poetry to Higginson along with her query:

Mr. Higginson,

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself—it cannot see, distinctly—and I have none to ask—

Should you think it breathed—and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude—

So began a friendship and correspondence that would last until Emily Dickinson’s death, after which, Higginson, along with the mistress of Dickinson’s brother Austin, Mabel Loomis Todd, would edit and assist in the publication of Emily Dickinson’s poems after her death. Dickinson personally sent Higginson over 100 of her nearly 1800 poems.

After the introduction describing Emily Dickinson’s first letter, Wineapple’s biography is divided into three major parts, titled “Before,” “During,” and “After,” which describe the lives of Dickinson and Higginson in alternating chapters before they began their correspondence, during their correspondence and friendship, and after Emily Dickinson’s death, respectively.

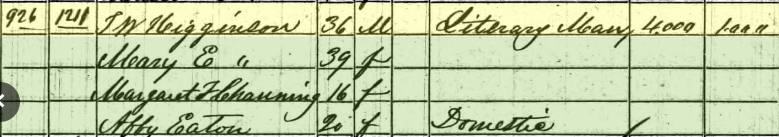

Emily Dickinson first wrote to Higginson while he was living in Worcester, Massachusetts, which is my home. I had to look him up on the 1860 US Census, and I was not disappointed.

Take a look at his occupation: “Literary Man.”

What Wineapple so expertly brings to light in this extraordinary biography is just how important Higginson’s contribution not only to preserving for posterity the poetry of one of the greatest American poets but also to history. Over time, he’s been accused of heavy-handed editing and of not understanding Dickinson’s genius. Both accusations may be true. One can hardly blame him for not understanding her. She was unlike any poet he had read before. Higginson himself claimed that “The bee himself did not evade the schoolboy more than she evaded me; and even at this day I still stand somewhat bewildered, like the boy” in an essay he wrote about Dickinson for The Atlantic, a magazine to which he was a frequent contributor. As to whether he was too heavy-handed an editor, Wineapple claims that it’s almost impossible to tell today whether it was Higginson or Mabel Loomis Todd who is more responsible for the edits. Thankfully, after the scholarship of Thomas H. Johnson and Ralph W. Franklin, we have editions of her poetry that more likely capture Emily Dickinson’s intentions. However, Wineapple does note that Higginson implored Todd on several occasions to “alter as little as possible, now that the public’s ear is opened.” Wineapple claims Todd “did not listen” (292).

In any case, Higginson’s reputation foundered with the advent of Modernism in the twentieth century, and while appreciation for Dickinson soared, Higginson was nearly forgotten. It’s a shame, too, because he was an admirable man. He was an abolitionist whose house was always on the Underground Railroad. He was an advocate for women’s rights and suffrage. It was he, not Robert Gould Shaw (now memorialized in the movie Glory) who led the first black regiment in the Civil War, the First South Carolina Volunteers. He suffered an injury that would leave a scar he carried all his life in an attempt to free fugitive slave Anthony Burns and prevent his return to the South.

Wineapple’s triumph in this biography is not only that she is able in some way to offer a peek into the lives of the Dickinson family, but also that she resurrected Higginson from “the dustbin of literary history” (12). As she explains in her introduction,

Sometimes we see better through a single window after all: this book is not a biography of Emily Dickinson, of whom biography gets us nowhere, even though her poems seem to cry out for one. Nor is it a biography of Colonel Higginson. It is not conventional literary criticism. Rather, here Dickinson’s poetry speaks largely for itself, as it did to Higginson. And by providing a context for particular poems, this book attempts to throw a small, considered beam onto the lifework of these two unusual, seemingly incomparable friends. It also suggests, however lightly, how this recluse and this activist bear a fraught, collaborative, unbalanced, and impossible relation to each other, a relation as symbolic and real in our culture as it was special to them. (13)

Wineapple’s book is not only one of the most interesting books about Dickinson to be found, but it is also one of the most well-written. I have rarely read a biography that swept me up in quite the same way this one did. I found myself both eager to pick it up to read, and reluctant to read too fast so that I could savor it and stretch out my experience of reading it. I came away with renewed appreciation for Dickinson and a newly acquired appreciation for Higginson. It’s definitely worth the read for anyone curious about Emily Dickinson, but I imagine even those who aren’t sure about Dickinson would enjoy this book.

Rating:

I bought this book in September 2015, I think right after I visited the Emily Dickinson Homestead the first time. I just now finally picked it up. It was published in 2008. I’m counting it for the Backlist Reader Challenge.

I bought this book in September 2015, I think right after I visited the Emily Dickinson Homestead the first time. I just now finally picked it up. It was published in 2008. I’m counting it for the Backlist Reader Challenge.